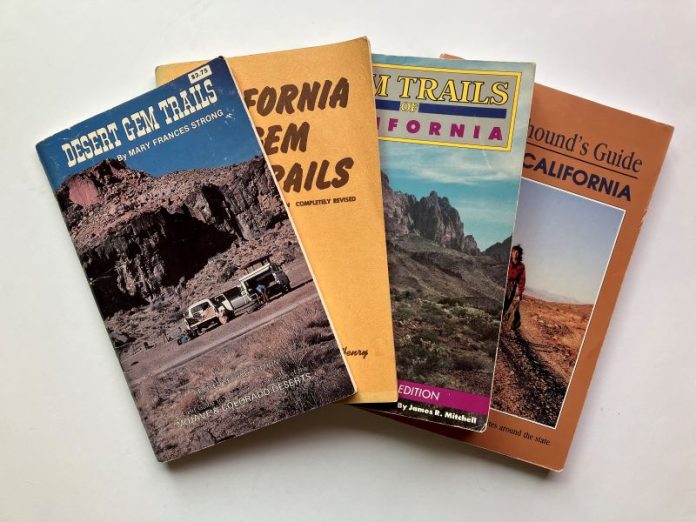

Rock collecting often means reading a field guide to get to a digging spot and identify what you find, but the results can be iffy.

“What do you mean, no road?” I asked my wife. I looked up from the map. We had been zig-zagging a rutted byway and had come to that fabled “End of the Road.” Ahead stretched boulders and untouched desert. Earlier, we had driven by a tumbleweed-lined exit off the main highway several times before we decided it must be the exit indicated on the guidebook map. The trouble was, the road itself was unmarked, and the only directions offered were “N off SR at ‘Bluebells’ sign, approx. 5 mi from intersection.” Unfortunately, that Bluebells sign apparently flew off in winds of long ago, and we found a choice of no less than four dirt roads (or at least what looked like roads) heading north off the State Route in the general vicinity of “5 mi from intersection.” We did not choose wisely. It was time to backtrack, and the morning was already well advanced. “We’re burning daylight,” I grumbled as Nancy put the truck in reverse and a cloud of hot dry dust wafted into my open window.

Sound familiar? Getting lost is part of the rockhound racket. Occasionally it pays dividends. Usually, it just burns daylight. To avoid this predicament, there exists the rock collecting guidebook. Good ones are a rockhound’s best friend. They list proven sites and save time locating them. Great rock-collecting guidebooks are updated periodically, provide annotated lists of further readings, and help identify finds with true-to-life illustrations or color photos of the rocks, minerals or fossils to be found. The very best provide geological context to better understand our finds.

Beware the Sin of Generality

While guidebooks are essential in a rock collecting toolkit, some are better than others. Those packaged with slick covers and huge four-color photos often provide more window dressing than instruction. Their glossy pics of Solnhofen limestone in Germany do you little good identifying your finds from Cincinnati. They can prove so general as to be worthless for anyone hoping to find a specific locality. For instance, consider a book with a spectacular 8×10 color photo of elbaite from Pakistan that merely says, “Tourmaline is to be found in Pala County.”

Don’t get me wrong. I love and respect guidebooks and those helpful souls who author them. They’ve taken my family on many a fun and productive adventure. But there are things to look out for when picking a guidebook. First, beware of those that communicate telegraphically, like the one Nancy and I regrettably took to the desert. For instance, consider the following: “On surface in SW part of state, in triangle bounded by Muiner Co. on N, state line in W.” Good luck finding an agate with those directions! When it comes to finding your way, the glory is in the details, and if authors can’t take time to write a complete sentence, do you think they took time to visit and check out the site?

Has the Author Been There?

This has become a crucial factor for me in trusting a rock collecting guidebook. In this age of build-baby-build, sites are gobbled up, old roads displaced, and buildings erected, so it’s virtually impossible for any guidebook authors to guarantee 100 percent accuracy. But it’s nice to know they’ve personally been there in the recent past and verified each site they list. The broader the scope (e.g., Fossil Collecting in North America), the less likely the author has been there and is providing detailed, first-hand information. What such books promise in scope, they lack in specificity. Rather than detailed directions to sites, you find tantalizing hints of “abundant, spectacularly preserved ammonites within Humboldt County.”

How Old is the Rock Collecting Book?

In addition to checking the degree of specificity and an author’s personal experience, check the copyright date. Don’t plan a long-distance trip to any locale listed in a guidebook over 10 years old without first double-checking. Often, that date is only the beginning of the story. Some guidebooks are outdated before they even come out because of reliance on secondary sources rather than direct experience of the author. One guidebook published in 1967 told of a “well-known” site in California with quartz crystals “in profusion.”

My collector’s urge went into overdrive only to literally hit a wall when I finally found myself in the Golden State and discovered nothing but houses in the very spot of this well-known site. Later, stumbling across the author’s original source in a geology library, I found he had pulled info from a 1951 guidebook. Like many authors of school textbooks, some guidebook authors simply copy from previous guidebooks and then get copied in turn.

Then again, I’ve also followed directions in a 1959 guidebook to fossils of Indiana and found sites that seemed just as productive as they must have been when the author sat down to a manual typewriter 65 years ago. The key point? Double-check, or have alternate plans in place, before making any extended trips to such locales. Nothing is more disappointing than arriving at a housing development, locked gates and no trespassing signs or a claim notice.

Check the Map & Double Check

While it’s only a general rule not to place complete trust in a rock collecting guidebook that’s showing its age, here’s an absolute rule: never trust a simplified map with only straight lines. In this day and age, GPS coordinates ought to be required. Getting from Point A to Point B with some guidebook maps reminds me of the Sidney Harris cartoon of two scientists staring at an enormously complex equation in the middle of which are the words, “then a miracle occurs.” “I think you should be more explicit here in step two,” says one to the other. You want to spend your time prospecting, not backtracking, so check the simplified schematic maps of guidebooks against a good detail map of the area before you hit the road. Even then, when venturing into the great unknown, caveat emptor! In the desert, backroads become washed out. Although freshly laid asphalt and concrete may look permanent, roads come and go in a geological instant.

Do Your Homework & Plan Ahead

Always do your homework. Don’t place complete trust in a rock collecting guidebook even if it fits the specificity criterion, seems up-to-date and has good maps. Consider checking ahead with local rock clubs or rock shops, state geological surveys, or regional Bureau of Land Management offices on the current status of a specific site. Sites can get played out, and especially significant areas (e.g., whole “forests” of petrified logs) have a way of becoming state or national parks or an Area of Critical Environmental Concern where all amateur collecting is prohibited. Homework saves heartache in the field.

Beware of Suspect Phrasing

When shopping for a guidebook, drill down deeper: read a sample entry and beware of passive sentence constructions. There’s a big difference between “A few emeralds have been found at this site” and “Emeralds are here.” A variation is may or might be found as opposed to can be or are found. There’s more than polite etiquette involved in asking “May fossils be found here” versus “Can I find fossils here?” Squishy language and passive sentence structures are notorious for concealing sad truths. Here’s an example from an actual guidebook: “Some dinosaur remains have been recovered from this area.” I read this in my younger days and my imagination went wild. I researched further and learned mining operations dredged up three unidentifiable bone fragments 150 feet below ground in 1872.

Alert readers also glean hints from commonly used rock collecting guidebook phrases that ought to raise red flags.

- the occasional rare piece = Good luck finding one!

- a great site for the elusive agate = One agate was found here in 1948.

- if you are extremely lucky = Only two specimens have ever been found here.

- four-wheel drive recommended =Accessible only by camel.

- typical desert road = Road? What road?

- an exciting, adventurous drive = Hold onto your hat!

- just a short walk = Hope you’ve got good hiking boots…

- with a little effort = You must pry your way through hard matrix. Dynamite helps.

- it is believed that = I’ve never actually visited this site.

- used to be found in abundance on the surface = You need to dig five feet down.

- as of this writing = Status of this site is iffy.

- there has been considerable collecting here = Ya shoulda been here 50 years ago!

- a pick and strong back needed = They treat chain gangs better!

- a good quarter of the geodes are great = 75% are duds.

- diligence and patience may be rewarded = Or maybe not?

- one should be in good shape, as should the car = We never did see Sam again.

On the positive side of the coin, a phrase like “be sure to take time to collect only the best” is a great indicator that good collecting material is plentiful.

Reading Between the Lines: Your Turn!

As an exercise in reading between the lines, try your hand at translating the following hypothetical guidebook entry that I only slightly modified from an actual entry. Then compare your translation to mine.

“Although Site A is in an area undergoing rapid development, as of this writing it is believed the diligent collector may still be rewarded. Rare specimens of fossil starfish may be found, and, with some patient effort, the careful collector may bring back a trilobite or two. More common are fragile brachiopods and numerous crinoid stems in the few thin, friable layers of shale between massive blocks of unfossiliferous limestone. At nearby Site B (four-wheel drive recommended), a few nice if poorly preserved marine invertebrates have been recovered from the upper part of the formation. There are still good specimens to be found by those willing to hike a little and search for it.”

My Translation?

I’ve never personally been to this site, but if you’re lucky and they haven’t buried it under an Amazon warehouse, your day might not be a total disaster. One specimen of a starfish and a trilobite were found when the area was first quarried in 1898 at a depth of 50 feet below the surface. Outcrops are now found in the area. The best you can really hope for are fragments of common crinoid stems.

If you possess the patience of Job, you might also pick a whole brachiopod from the few crappy layers of shale that will take three hours to find. A similar site with much poorer offerings is only four miles away as the crow flies but really 18 miles by the time you wind your way across a ravine, around two mountains, and over rutted remains of a former road. Good luck. (You’ll need it!)

Here’s to Good Hunting!

I invite your translation of our not-so-hypothetical rock collecting guidebook entry. Perhaps together we can make sense of the common guidebook. Then armed with the right guidebook, a proper dose of skepticism, good humor, and—above all—foresight and planning, set out with confidence and return with a beauty. Here’s to good hunting and here’s to all those helpful and well-intentioned guidebook authors who have taken the time to assist us. It really is appreciated!

This story about rock collecting field guides appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Jim Brace Thompson.