By Steve Voynick

The bright-white color that we see in everything from highway lines, donut icing, and toothpaste to paint, paper, plastics, and ceramics comes mostly from titanium dioxide, the world’s most widely used pigment. Titanium dioxide, better known as “titanium white,” originates, oddly enough, with the black mineral ilmenite.

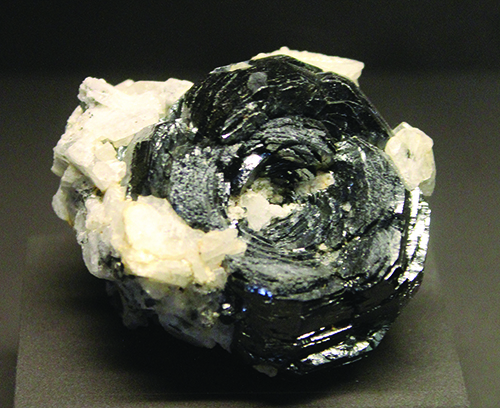

Named for its type locality in the Ilmen Mountains (Ilmensky Mountains) of Russia’s southern Urals, ilmenite is iron titanium oxide (FeTiO3). An abundant mineral that crystallizes in the trigonal system, ilmenite usually occurs in massive or granular forms and occasionally as the tabular crystals sought by mineral collectors. Black, opaque, weakly magnetic, and exhibiting a metallic-to-submetallic luster, ilmenite has a Mohs hardness of 5.5-6.0 and a substantial specific gravity of 4.7-4.8.

Pioneer of Magma Solidification

As one of the first minerals to crystallize from solidifying magma, ilmenite’s density enables it to concentrate in layers at the bottom of magma chambers through the process of magmatic segregation. Solidification usually produces igneous masses with ilmenite-enriched layers. Then, as the host rock eventually weathers and erodes, the freed ilmenite particles concentrate in alluvial deposits. Placer miners know that the black sands in gold-pan and sluice concentrates often consist largely of ilmenite.

Titanium, the ninth most abundant element in the earth’s crust, is a strong, lightweight metal used in high-performance alloys. The most common titanium-bearing mineral, rutile (titanium oxide, TiO2), does not form deposits rich enough to mine. But ilmenite, the next most abundant titanium-bearing mineral, does occur in concentrated deposits and is the primary ore of titanium.

Ilmenite is mined on the surface, occasionally from in situ igneous rock formations but mainly from beach and inland sand deposits. Titaniferous (titanium-bearing) sands consisting mainly of ilmenite with smaller amounts of rutile are mined with earth-moving equipment, then concentrated by simple hydraulic separation.

Only about five percent of ilmenite is used to produce metallic titanium. The remainder is converted into titanium dioxide (synthetic rutile) — the pigment called titanium white.

Chemists discovered the extraordinary pigmentation properties of titanium white in 1821. At that time, the pigment was obtained only by grinding rutile into a fine powder. But the limited rutile supply sharply curtailed the production of titanium white.

In 1916, researchers learned to convert ilmenite to titanium dioxide cheaply. That knowledge opened the door to mass production of titanium white and made titaniferous sands a valuable ore.

Titanium’s Invaluable Role in Pigmentation

Titanium white is unmatched as a white pigment. It has a pure, snow-white color and is highly reflective. With its extremely high refraction index — 2.614 (higher than that of a diamond) — ilmenite scatters light to provide excellent opacity. In paints, opacity translates to “hiding power,” or a thin layer’s ability to completely mask the color of a substrate.

Titanium white is also added to most other pigments to modify the color and enhance brightness and opacity. In manufacturing, the particle size of titanium white can be easily controlled for specialized pigment requirements.

Titanium white is chemically inert and does not alter even with prolonged exposure to sunlight. And being non-toxic, it is safe to ingest and is added to many food products to create white-ness, modify color, or enhance opacity.

Nearly eight million tonnes (metric tons) of titaniferous sands are mined worldwide each year, mostly in Australia and China. With only two titaniferous-sand-mining operations, the United States is a minor producer and imports 90 percent of its titanium white. Crude titanium white now costs $175 per tonne, and the U.S. uses 834,000 tonnes each year — roughly five pounds for each person in the nation.

Millions of ilmenite tonnes are mined annually from sand deposits. But collectible specimens come only from granite pegmatites. The most desirable specimens feature dark rosettes, platy masses, or tabular crystals of black ilmenite resting atop contrasting white matrices of albite or quartz.

Its black color notwithstanding, ilmenite brightens our world through titanium white.

If you enjoyed what you’ve read here we invite you to consider signing up for the FREE Rock & Gem weekly newsletter. Learn more>>>

In addition, we invite you to consider subscribing to Rock & Gem magazine. The cost for a one-year U.S. subscription (12 issues) is $29.95. Learn more >>>