By Steve Voynick

There always seem to be points of interest along the Interstate Highway System, even in the most unlikely places. Consider the remote junction of Interstate highways 15 and 70, located 23 miles from the nearest town in the wide-open, sagebrush-and-cedar country of southwestern Utah.

Marked by exit signs and just two miles from the highway junction is the ghost town of Sulphurdale. During the 1890s, Sulphurdale was the biggest source of sulfur in the United States; today, it’s the home of a modern geothermal power plant.

Sulfur Source and Ghost Town

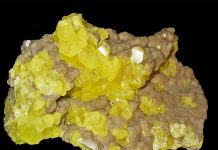

Pioneers in the 1850s often visited this site, which was known for hot springs that bubbled from depressions ringed with crusts and layers of bright-yellow, elemental sulfur. Disregarding the distinctive—and distinctly unpleasant—odor of the hydrogen-sulfide gas that emanated from the springs, they gathered and sold the sulfur for use in making gunpowder.

In 1869, mine developer Ferdinand Dickert surveyed this deposit and found it large enough to be commercially mined. In 1883, he built a small thermal-extraction furnace that heated the sulfur ore in an oxygen-deficient environment to produce molten sulfur.

Dickert’s mine was soon producing 1,000 tons of sulfur per year. By 1893, the company town of Sulphurdale boasted 30 homes, a general store, and a school, along with a mine-office building and blacksmith shops. That year, Sulphurdale provided the nation’s entire domestic supply of sulfur.

Sulfur Production

Sulphurdale rests atop heavily faulted bedrock near a volcano that was active in recent geological time. The shallow magmatic body that created this volcano also forced superheated water that was rich in dissolved hydrogen sulfide upward and into shallow beds of porous volcanic tuff. There, the water cooled, and elemental sulfur precipitated out in massive and disseminated forms, and occasionally as small, translucent, bright-yellow crystals.

Sulphurdale produced sulfur intermittently until the 1950s. In its final years, miners tested flotation-separation and chemical-solvent recovery methods in an effort to remain competitive. But in the end, Sulphurdale lost out to the cheap sulfur coming from the new Frasch mines in Texas and Louisiana, which melted deep sulfur deposits with superheated water to recover industrial quantities of molten sulfur.

Although the estimated quarter-million tons of high-grade sulfur ore that remain in the ground at Sulphurdale are unlikely to ever be mined, the geothermal water that emplaced it is being utilized. Sulphurdale is now the site of a $125 million, geothermal power plant owned and operated by Enel Green Power North America Inc.

The plant taps a deep steam reservoir and pumps hot water to the surface. In a “binary cycle” operation, this water passes through heat exchangers to heat a hydrocarbon fluid to its very low boiling point. As this volatile fluid boils, its vapors drive turbines to generate electricity. The now-cooled geothermal water then flows into return wells and back into the deep, subterranean steam reservoir to be naturally reheated and recycled. With an annual capacity of 160 gigawatt hours, the plant provides power for industry and for thousands of residences in the city of Provo, Utah, 140 miles to the north.

Power and Past

The plant road through the site of Sulphurdale passes the long-abandoned mine office building, the ruins of loading docks, exposed ledges of yellow sulfur ore, and the shallow open pit where mining began 134 years ago.

As an active industrial site, Sulphurdale is not an open mineral-collecting locality.

All visitors must report directly to the plant control room. When my wife and I did this, we got permission to explore and photograph the ruins.

Author: Steve Voynick

A science writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhounding.”

A science writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhounding.”

Learn more about Mr. Voynick from his site: Mountain Press Publishing.