Vanadium is a versatile element best known for its role in strengthening steel, but it also forms the basis of more than 150 colorful minerals that appeal to collectors and geologists alike. While vanadium’s industrial applications are far-reaching, its mineral forms—many of them vividly hued—are just as fascinating.

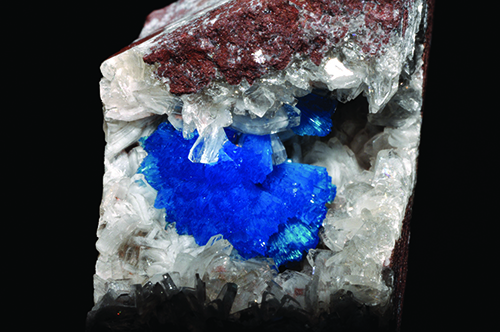

Among vanadium-bearing minerals, collectors are especially drawn to vanadinite, mottramite, and cavansite. Vanadinite, lead chlorovanadate, forms striking orange-red hexagonal prisms and is the most collectible. Mottramite, a basic lead copper vanadate, is prized for its greenish-yellow encrustations and botryoidal structures. Cavansite, a hydrous calcium vanadium oxysilicate, captivates with its brilliant blue spherical aggregates.

Vanadium’s Chemical Connection to Uranium

Because of a mutual chemical affinity, about a third of all vanadium-bearing minerals contain uranium. These include carnotite, a hydrous potassium uranium vanadate, and tyuyamunite, a hydrous calcium uranium vanadate, both of which occur as bright, canary-yellow encrustations.

Elemental vanadium is not as showy as many of its minerals. It is a silvery-white metal as dense as iron, but with a substantially higher melting point. Ranking 19th in crustal abundance, it is about as common as chromium and nickel.

Although relatively ductile and malleable, it is one of the hardest of all metals at Mohs hardness 7.0. Because of its affinity for oxygen, elemental vanadium is rare in nature and has been found only as a sublimate in the cone of Mexico’s Colima Volcano.

In 1801, Spanish mineralogist Andrés Manuel del Río proposed the existence of a previously undiscovered metal in a mixture of lead minerals, an observation confirmed in 1830 by German mineralogist Friedrich Karl Wöhler. The following year, Swedish chemist Nils Gabriel Sefström, experimenting with iron ores, extracted a colorful oxide of this mysterious metal from which he produced other brightly colored compounds. Sefström named this still-unseen metal “vanadium,” after Vanadis, one of the names of the Norse goddess of beauty, alluding to its colorful compounds.

Vanadium’s Market Evolution

Elemental vanadium was finally isolated in 1867 as a laboratory curiosity obtainable only in small quantities from vanadinite and as a by-product of iron smelting. In 1890, French metallurgists discovered that small amounts of vanadium enhanced the hardness, tensile strength, toughness, and corrosion-resistance of steel. Steelmakers, however, were hesitant to adopt vanadium-steel alloys. As demand slowly grew, a Peruvian deposit of patrónite (vanadium sulfide) became the first commercial source of vanadium in 1901.

Industry-wide acceptance of vanadium-steel alloys came about through the work of the pioneering American automobile manufacturer Henry Ford. While seeking materials for his Model T automobiles in 1910, Ford inspected a European racing car that had crashed at the new Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The impact had bent or fractured all its chassis and power-train components—except for the crankshaft, which consisted of a new vanadium-steel alloy.

The vanadium in those Model Ts came from Colorado carnotite ore and mill tailings, which had originally been mined for their tiny radium content. Patrónite and carnotite are the only minerals ever mined as primary ores of vanadium.

Today, vanadium is obtained as a by-product of processing vanadiferous iron and titanium ores, iron slags, and petroleum residues. Of the 80,000 tons of vanadium recovered worldwide each year, 95 percent is alloyed with steel. In ready-to-alloy, elemental form, vanadium sells for about $10 per pound.

Vanadium: Industrial and Metallurgical Uses

Vanadium-steel alloys are used in pipeline sections, high-speed tool steels, and structural steel girders. Vanadium-chrome steels are standard in automotive suspension springs, transmission gears, and high-stress engine components, while lightweight, heat-resistant vanadium-aluminum-titanium alloys are vital in heat-resistant components of jet and rocket engines.

Vanadium Final Thoughts

Knowing a bit about vanadium’s history and how it’s used makes those colorful crystals—like vanadinite, mottramite, and cavansite—even more fun to collect. There’s something about holding a mineral that’s not just beautiful, but also part of a much bigger story in science and industry.

This Rock Science column about vanadium previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Column by Steve Voynick. Click here to subscribe.