Selenium is an essential nutrient, but did too much of a good thing cripple horses at the Battle of Little Bighorn and hinder the army’s progress?

Selenium was first identified as a chemical element in 1818 by the Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius, after noting how light-excited electrons were found in the residue of a sulfuric acid vat. Today selenium is also known as a nutritional trace element. Its chemical nonmetal status can still be seen utilized all around us, including in the familiar red of warning signals and tail lights. That’s not, however, the first time selenium has been associated with a red flag.

The Good, The Bad & The Ugly

Reports of selenium’s woeful toxicity and deleterious effects on horseback travel date back to the 1295 journal of Venetian explorer Marco Polo. He cursed what would now be called a selenium accumulator growing in western China as he traversed the borders of Tibet and Turkestan: “A poisonous plant… which if eaten by (horses) has the effect of causing the hoofs of the animal to drop off.”

By 1860, selenium had been identified in military annals as a “toxic principle causing lameness and death” in livestock grazed on certain range plants in the Dakotas and Wyoming.

That was just 16 short years before Custer, 225 cavalry horses, and roughly 150 mules would ride out from Fort Lincoln in Bismarck for the last time. To the south, at Fort Randall, abutting South Dakota and the northern border of the Nebraska Territory, there were reports lamenting horses suffering with “alkali diseas.” These horses showed hair loss, skin lesions and hoof inflammation “followed by suppuration at the point where the hoof joins the skin and ultimate loss of the hoof.” Crippled horses were unable to forage for food or water and inevitably starved to death.

For Want of a Nail

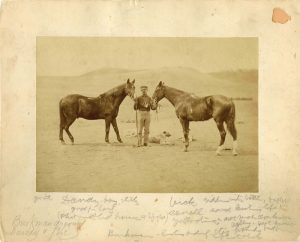

Courtesy of History Nebraska.

Early attributions to alkalinity would prove a misnomer. The disease was selenium poisoning that could both cripple animals and an army’s efficiency and progress.

“In campaigning against the Indians of the Plains, Custer and his frontier cavalry could fight but was anchored to his ration supply: the pack train,” wrote John S. Gray, in a 1976 article for Nebraska History. “There were ‘professional’ pack trains at this time, but the cavalry did not use them, instead employing its own soldiers to pack, operate, and guard the train.”

Albeit not solely to blame for the defeat, Custer’s inefficient cobbling together of a battle-ready pack train from in-house reserves did, Gray surmised, “drain off fighting men and contribute to the scattering of the regiment.”

Three Column War

To wage this war required three columns – General Crook’s Wyoming column, General Gibbons’ Montana column, and General Terry’s Dakota column, which included Custer and the 7th Cavalry. Their amateur trains did not inspire confidence.

The slow and sore pack train ultimately drained 22% of the manpower in Custer’s fighting ranks and lagged far behind, holding back critical reserve ammunition.

“The horses were under saddle the greater part of daylight each day to average 17 miles in 24 hours. Such marching is most trying on cavalry, as it breaks animals down to no purpose,” wrote Major Alfred E. Bates wrote in The Second Regiment Cavalry I for the U.S. Army Center of Military History.

“Much of Crook’s cavalry was in bad condition when he met Terry. By the time the mouth of the Powder was reached many horses in each column were hors de combat (out of action).”

Horses in Bad Condition

Custer was referenced in 2007, in a book about laminitis and founder (severe hoof diseases) by farrier Dr. Doug Butler and veterinarian Dr. Frank Gravlee, who put forth an interesting footnote from a rarely published agricultural (not military) historical source. In “History Mystery,” for Hoofcare.blogspot.com, Fran Jurga recounted, “They quoted a report published in a 1944 journal, Agricultural History, stating that Custer’s horses had been wintered on fields known for heavy growth of highly selenium-rich plants and soil.”

Cornell University equine nutritionist Harold Hintz reignited the conversation about selenium toxicity and Little Bighorn further. In a 2000 abstract co-authored with L.J. Thompson, he directly mentioned lameness problems among Custer’s late-arriving pack train. He proposed that the animals suffered from not one, but two forms of toxicity. Selenium was responsible for the lameness issues. A second toxin, swainsonine, aka ‘loco weed,’ contributed to the unmanageability of the animals and also hindered progress.

Could Defeat Have Been Avoided?

Hintz and L.J. Thompson’s “Custer, Selenium and Swainsonine” said that among controversies remaining around the century-old battle were feelings that defeat could have been avoided if the other troops had united with Custer sooner. They proposed: “A slow-moving pack train may have hindered the troops from joining up. One report indicated the horses and mules in the pack train were lame and behaved crazily. The lameness could have been caused by selenium (and) behavioral problems may have been caused by ingestion of plants containing swainsonine.”

A certain proverb about sound horses and successful battles should have warned how innocuous acts —like blithely grazing horses — can have grave consequences.

“For want of a nail the shoe was lost/For want of a shoe the horse was lost/For want of a horse the rider was lost/Being overtaken and slain by the enemy/All for want of a nail.”

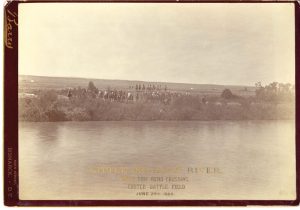

The Greasy Grass

An ongoing research project by the U.S. Department of Agriculture has been identifying selenium-accumulating (up to 3000 parts per million) plants growing today in Colorado, Montana, North and South Dakota, Utah and Wyoming. In addition to high selenium in the soil, water and plants, these states share common denominators of 20 inches or less in average rainfall and alkaline soil with a pH of seven or more.

But in Custer’s day, the U.S. Army was only just beginning to recognize, much less understand, selenium toxicity.

It was a problem already familiar to – and studiously avoided by – Plains tribes, including the Arapaho, Cheyenne and the Lakota Sioux that the 7th Cavalry sought in battle.

The Lakota translation for the river, and prairie ridges and ravines that white settlers called Little Bighorn, was darkly prescient. It was called The Greasy Grass, after the slick, unappetizing look to the blades of grass along its banks. This grass, with a particularly resilient root system is capable of storing nutrients for use in stressful times like droughts and fires. This is where a mineral, like selenium, might survive if not thrive.

Avoiding Local Grazing

Even Sitting Bull, the political and spiritual leader of the Sioux, (later gifted a trick horse named Rio by Buffalo Bill Cody in honor of his horsemanship) avoided wintering herds along its banks. He later had a vision of bluecoats and horses falling “like grasshoppers” in the Greasy Grass.

“Custer was supposed to drive the 7th Cavalry along the Rosebud and go west, along a trail created by the Lakota and Cheyenne, and push them toward General Terry coming from the north, expecting to drive them into a two-arm pincer from which the indigenous soldiers could not escape,” writes Pekka Hämäläinen in Lakota America: a New History of Indigenous Power.

The last thing Crow scout, Half Yellow Face, said to Custer before riding out that morning was, “You and I are going home today by a road we do not know.”

Looking Back, Moving Forward

Five years ago, biogeochemist Lenny Winkel, at the Department of Environmental Sciences at ETH Zurich and Eawag, began mapping the global distribution of selenium and factors determining where it occurs.

What it reveals is an elusive moving target. “The concentration of selenium in the soil is different from one region to the next,” Winkel says. “[Even] in plants, selenium content varies greatly according to where they grow.”

Custer, without having lived with the land and water of the tribes he sought to displace, never stood a chance of identifying where it might have been safe to graze his animals.

Essential Nutrient & Toxicity

“Selenium is an essential nutrient and is important in muscle function,” says Scottish researcher and equine hoof health expert, Dr. Susan Kempson, with the Department of Preclinical Veterinary Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. Unlike most minerals with a broad safety range, selenium has a very low threshold of toxicity for horses.

Selenium still runs a highly toxic risk, she says, citing a tragic case in Florida in 2009 when inadvertent overdoses of selenium in a vitamin/mineral supplement led to the collapse and death of 21 imported polo ponies. “Horses only need one part per million (ppm) of selenium in their diet (cattle need 20 ppm). Feeding copper can protect horses with low-level excess selenium in their diet but the mechanism for this is still unknown.”

Today, many people walk where the horses and soldiers walked at Little Bighorn Battlefield on the Crow Agency in Montana. How many know how a little mineral wrote a big footnote to history?

Stories in Its StonesExplore the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument memorializing the US Army’s 7th Cavalry and one of the last armed efforts by Plains Indian tribes to preserve their way of life. Walk or drive a 4.5-mile self-guided tour and visit Deep Ravine Trail, Custer’s Last Stand Hill, the 7th Cavalry Monument and the Indian Memorial. The park is open daily from 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Learn more at www.nps.gov/libi/index.htm. |

This story about selenium and its impact on the Battle of Little Bighorn appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by LA Sokolowski.