Shakespeare’s jewelry and gemstones mentioned in his writing serve as metaphors for wealth and beauty and as words that evoke images and emotions. Here’s what you need to know about collecting these Elizabethan gems.

…of amber, crystal and beaded jet

…for thy mind is opal

…his heart like an agate

…and rubies red as blood

These lines from the plays and poems of William Shakespeare are just a few of many that reflect his awareness and extensive poetic use of gemstones.

Shakespeare’s Jewelry By Words

In his 37 plays and 154 sonnets, Shakespeare uses the terms “crown,” “ring,” and “bracelet” (which one assumes are set with gemstones) some 400 times, and “precious stone” and “jewel” around 300 times. He also mentions specific gemstones and gem materials more than 100 times.

If the frequency of usage is any indication of Shakespeare’s personal gemstone preferences, he was most enamored of pearls, which he mentions 43 times, followed by diamonds at 22 times.

Shakespeare also refers to garnet, ruby, agate, amber, jet, carbuncle, emerald, turquoise, opal, rock crystal, sapphire, and chrysolite, most of which were popular gemstones and gem materials during England’s Elizabethan Era when Shakespeare did most of his writing. Examining the sources, value, and importance of these gemstones is a window into life during Elizabethan times.

About William Shakespeare

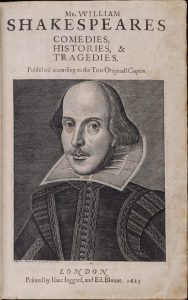

author was published in 1623. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

William Shakespeare was born in 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England, a village 90 miles northwest of London. While in his 20s, he became an actor, writer, and part-owner of an acting company; he went on to produce most of his work between 1589 and 1613. Although not widely acclaimed at the time of his death in 1616, he is today recognized as arguably the greatest writer in the English language.

The Elizabethan Era, which coincides with the 1558-1603 reign of Queen Elizabeth I, is considered England’s “golden age.” It marked a renaissance in art, music, theatre, and literature and was a time when many English citizens were intrigued by gemstones. The concept that gemstones set into royal crowns and scepters signified wealth, power, and authority was well-established in England by 1000 CE.

Queen Elizabeth I’s father, King Henry VIII, who reigned from 1509 to 1547, had a particular fondness for gemstones; his seven-pound, golden crown was studded with 344 gems and pearls. His daughter was equally fond of gemstones and gem-studded jewelry.

Science vs. Medieval Beliefs

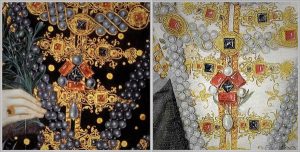

Elizabeth I, painted about 1590, shows the Three Brothers gem ensemble diamond, spinel and pearls in the center.

STEVE VOYNICK

The Elizabethan Era was part of the long transition period between medieval beliefs and the age of science, and its perception of gemstones was rather complex. Then as now, gemstones were statements of fashion and wealth. But in Shakespeare’s time, with mass education far in the future and illiteracy the norm, gemstones were also closely linked with medicine, folklore, and religion. And with science only in its rudimentary stages, belief in gem-related miracles and superstitions was common.

It is unknown whether Shakespeare personally possessed any of the gemstones about which he wrote. But he certainly saw many fine gems in pageants and processions during the years he lived and worked in London. His acting company also performed at royal functions where elite attendees were well-adorned with costly gems and jewelry.

Shakespeare’s Jewelry – Pearls

Shakespeare writes most often of pearls, which were hugely popular in Elizabethan England and the favorite of Elizabeth I. Shakespeare frequently associates pearls with dewdrops and tears, as in Richard II when he writes: “The liquid drops of tears that you have shed/ Shall come again transformed to orient pearl.” The term “orient pearl” referred to an especially fine pearl from the Red Sea, Persian Gulf, or the coast of India. Shakespeare seems aware of these sources, for in Troylus and Cressida, he writes: “Her bed is in India, and there she lies, a pearl.” Today, the term “orient” refers to the luster and color of a quality pearl.

Troylus and Cressida also provides an example of Shakespeare’s metaphoric use of pearls: “She is a pearl whose price has launched o’er a thousand ships.”

Elizabethan royalty wore pearls as jewelry and also as decorations on cloaks and robes. In Henry V, Shakespeare describes one such garment as “an intertissued robe of gold and pearl.” In royal portraits of Elizabeth I, her gowns are often studded with hundreds of pearls.

While the best pearls then came from the “Orient,” many of those available in Elizabethan England were freshwater pearls of somewhat lesser quality from the rivers of Scotland.

Literary Gems – Diamonds

In Shakespeare’s time, diamonds came only from the Pannar and Krishna rivers in what is now India’s Andhra Pradesh state. Although Indian diamonds reached Europe during the time of the Roman Empire, the trade did not resume again until about 1600 with the founding of the British East India Shipping Company. By then, Indian diamond mining was a major industry that employed 30,000 workers and the Indian treasury held 135,000 carats of uncut diamonds, none weighing less than 2.5 carats.

At that time, diamonds were valued less for their beauty than for their rarity, extraordinary hardness, and mystique of distant origin. Precise, symmetrical faceting as we know it today did not yet exist. Large diamonds were crudely shaped, partially faceted, or cleaved into octahedrons; smaller diamonds were set in the rough into rings and crowns.

Diamonds in England

Although few great diamonds reached England, those that did attracted the attention of many, including Shakespeare. One such diamond was the centerpiece of what came to be known as the “Three Brothers” gem ensemble. Fashioned in Paris around 1400, it featured a large, pyramidal-cut diamond, surrounded by three rectangular, red gemstones and four large pearls. The Three Brothers became part of the British Crown Jewels in 1551 and is seen in several portraits of Elizabeth I.

In the early 1600s, the value of this pyramidal diamond was stated at 7,000 English pounds, roughly the equivalent of $1.3 million in today’s U.S. dollars. Unfortunately, the Three Brothers disappeared about 1645; its fate remains unknown. In his plays, Shakespeare employs diamonds as royal gifts or as metaphors for great beauty and value. Their monetary value is inferred in The Merchant of Venice when the moneylender Shylock laments the loss of his diamond: “Why there, there, there, there, a diamond gone!/Cost me two thousand ducats in Frankfort!” That sum is roughly the equivalent of $140,000 today.

Turquoise – “Turkies”

Shylock also laments losing a turquoise of great sentimental and monetary value: “It was my turquoise/I had it of Leah when I was a bachelor.” This is Shakespeare’s only mention of turquoise.

Although the gemstone had been mined for thousands of years in Persia (present-day Iran) and in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, it was costly and rarely seen in Elizabethan England. Shakespeare, who seems to value this gemstone nearly as much as a diamond, refers to it in his original texts as “turkies”—the English root of our modern word “turquoise” and an allusion to the gemstone routes that passed through the country of Turkey.

Shakespeare also mentions the medieval custom of sacrificing gemstones to thank or beg favors from higher powers. After almost drowning, the queen in Henry VI says, “I took a costly jewel from my neck/A heart it was bound in with diamonds/And threw it towards the land/The sea received it.”

Shakespeare’s Jewelry – Amber

STEVE VOYNICK

Lesser gemstones are sacrificed in Shakespeare’s narrative poem A Lover’s Complaint: “A thousand favors from a [basket] she drew/Of amber, crystal, and beaded jet/Which one by one she into the river threw.”

Amber, rock crystal, and jet all enjoyed great popularity in Elizabethan England. Amber, a polymerized fossil tree resin, came from the southern beaches of the Baltic Sea, where it had been collected since antiquity. Large quantities of amber reached England in trade during the Elizabethan Era.

Shakespeare’s Jewelry – Rock Crystal

Rock crystal, or “crystal” in Shakespeare’s usage, the colorless, transparent form of macrocrystalline quartz, was far more valuable in Shakespeare’s time than it is today, and was set in crowns and jewelry side-by-side with precious gems. Although lacking a diamond’s sparkle, it was much more workable and affordable. A steady supply of rock crystal was obtained from England’s Northumberland and Cumberland areas.

Shakespeare’s “crystal eyes” and “crystal tears” are metaphors for brilliance, transparency, cleanliness, or clarity, as in Richard II: “The more fair and crystal is the sky/The uglier seem the clouds that in it fly.” In Romeo and Juliet, he infers that a lady’s love should be measured on “crystal scales,” meaning with great clarity of thought. Our modern expression “crystal clear” derives directly from Shakespeare’s metaphoric use of the word “crystal.”

Shakespeare’s Jewelry – Jet

gemstone often mentioned by Shakespeare. STEVE VOYNICK

And England also had the world’s premier source of jet at Whitby on its eastern coast. A form of lignite coal that occurs in small pods rather than seams, jet is fine-grained, lightweight, durable, easily workable, and takes an excellent polish. In The Merchant of Venice, jet is used to create a sharp contrast: “There is more difference between thy flesh and hers/Than between jet and ivory.” And in Henry VI, Shakespeare describes a gown’s color as “Black, forsooth, coal-black as jet.” Our descriptive term “jet-black” also stems from Shakespeare’s comparative use of the word “jet.”

Shakespeare’s Jewelry – Red Gemstones

Shakespeare’s red gemstones are “rubies” and carbuncles. “Carbuncle” then referred loosely to moderately hard, red gemstones, but especially to garnet. Red gemstones harder than garnet were specifically called “rubies.”

While a limited number of true rubies—the red gem variety of corundum (aluminum oxide)—reached Elizabethan England, most hard, red gemstones were actually spinel (magnesium aluminum oxide). The British and Dutch East India companies only began bringing quantities of true ruby from Southeast Asia to Europe around 1600. True ruby was not even mineralogically differentiated from spinel until 1783.

Spinel

Shakespeare uses “ruby” only as an adjective for a bright or rich shade of red. In Measure for Measure, he compares rubies to blood when Isabella says “the impression of keen whips I’ll wear as rubies.” Spinel was then known as “balas ruby,” from the Arabic Balakhsh for its source near the present-day Afghanistan- Tajikistan border. Balas rubies were well-known in Elizabethan England, thanks to the fabled Black Prince’s Ruby.

According to legend, this two-inch, 170-carat, irregular cabochon was taken by Don Pedro, the King of Castile, from the Muslim prince of Granada in 1367. Don Pedro later passed it on to Edward of Woodstock, known as the “Black Prince.” The gem appears in Henry VIII’s 1521 crown jewel inventory as the “large ruby” set in the Tudor Crown. Although later mineralogically identified as spinel, the Black Prince’s Ruby has nevertheless retained its traditional name.

Pyrope Garnet

Shakespeare would also have been familiar with the “rubies” in the previously mentioned Three Brothers gem ensemble, in which the “brothers” are actually three large, rectangular-cut spinels. Shakespeare’s “carbuncle” is pyrope garnet. With its deep-red color and relative affordability, carbuncle had been a favorite gemstone in England since Anglo-Saxon times. During the Elizabethan Era, it served as a standalone gem in rings and a cloisonné inlay in gold jewelry.

At that time, pyrope came from the Ceské Stredohorí Mountains north of Prague in the Bohemia region of the present-day Czech Republic. This pyrope had weathered free from peridotite host rock and concentrated in vast alluvial deposits. This was the world’s first great Pyrope source and its type locality; some deposits are still being mined there today.

Carbuncle

In Elizabethan superstition, carbuncle generated its own internal light. Shakespeare apparently shared this view, for he uses carbuncles as the glowing eyes of ominous figures as in Hamlet, when he describes the “hellish” Pyrrhus as having “eyes like carbuncles.” Carbuncle remained synonymous with red garnet for centuries. The word “pyrope,” which first appeared in the English language in 1804, fittingly stems from the Greek pyršpos, meaning “fiery-eyed.”

Although Shakespeare usually mentions gemstones to project beauty, wealth, power, and mystery, an exception is found in the Comedy of Errors when he ironically describes a blemished nose as “all o’er embellished with rubies, carbuncles and sapphires.”

In this line, Shakespeare makes a clear distinction between ruby and carbuncle. It is also the only mention of sapphire in his plays. Sapphire then came from the island of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Shakespeare’s only other mention of sapphire is in A Lover’s Complaint where it is described as “heaven-hued,” reflecting the belief at the time that all sapphires were blue.

Agate Popularity

Another popular Elizabethan gemstone was agate. Most agate during this time was engraved with human likenesses and mounted in rings that were especially popular among merchants and aldermen. Agate then came from Europe’s leading gem-cutting center at Idar-Oberstein, Germany. In Love’s Labour’s Lost, Shakespeare compares engraved agate to a lover’s heart: “His heart, like an agate, with your print impress’d.”

Emerald Green

Shakespeare rarely mentions emeralds and only then as an adjective for a vivid shade of green. Until the early 1500s and the Spanish colonization of the New World, emeralds came only from Egypt’s historic mines. And these were pale and clouded, not something that Shakespeare would have chosen as a metaphor for green. But he likely had been familiar with the vividly colored, transparent emeralds just then reaching Europe from Spain’s Viceroyalty of Peru (modern Colombia).

In A Lover’s Complaint, Shakespeare alludes to the ancient belief that emeralds cured eye ailments: “The deep-green emerald in whose fresh regard/Weak sights their sickly radiance do amend.”

Shakespeare’s Jewelry – Amazing Opals

One of Shakespeare’s best-known lines in Twelfth Night is: “ . . . and the tailor make thy doublet of changeable taffeta/For thy mind is opal.” The Clown is comparing the Duke’s vacillating mind to opal’s constantly changing, opalescent colors.

Until the discovery of Mexican and Australian opal in the 1800s, the world’s only significant opal source was Cervenica in the Prešov region of present-day Slovakia. In Elizabethan times, Cervenica opal was very costly and considered especially lucky because its multicolored opalescence was thought to have captured the virtues of every other colored gemstone.

Chrysolite Equals Beauty & Value

In Othello, chrysolite is a metaphor for beauty and value: “If heaven would make me such another world/Of one entire and perfect chrysolite/ I’ld not have sold her for it.” Shakespeare’s “chrysolite” was actually peridot (forsterite, magnesium silicate) which had been mined since Roman times on Egypt’s Zabargad (St. John’s Island) and was still occasionally mined during the Elizabethan Era.

Shakespeare’s frequent use of gemstones in his plays and poems provides striking imagery and insight into the Elizabethan perception of gemstones. Two excellent sources on Shakespeare and his literary use of gemstones are Shakespeare’s Gemstones by David W. Berry (privately printed, 2004); and Shakespeare and Precious Stones by George Frederick Kunz (J. B.nLippincott, 1913, Project Gutenberg E-book reprint, 2005). Both are accessible online in their entirety.

This story about Shakespeare’s jewelry and gemstones previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe! Story by Steve Voynick.