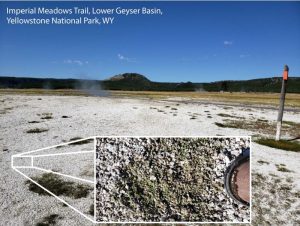

Sinter geyser eggs were churned up when eruption activity started increasing at Yellowstone National Park in May 2023 at popular sites like Snow Globe Geyser, Geyser Hill and Old Faithful.

What is Sinter?

What exactly is sinter and what role do hydrothermal eruptions play in its production?

Quite a bit, actually, says the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory (YVO) – a consortium of nine state and federal agencies who monitor and provide hazard assessment of volcanic, hydrothermal and earthquake activity in the Yellowstone Plateau – and the U.S. Geologic Survey (USGS) arm of YVO responsible for monitoring volcanic activity in the intermountain western states.

According to the Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles, published weekly by YVO scientists and collaborators, what we know about how heat, water, gas and rock interact to create the diverse fluids found at the park’s thermal features can be credited to the diligence of two turn-of-the-20th-century geologists: Arthur Day and Eugene Allen with the Geophysical Laboratory at Carnegie Institute in Washington (CIW). Having published a book on volcanic and hydrothermal geology at Lassen Peak in California, they set off to conduct similar studies at Yellowstone, yielding two seminal papers on hydrothermal circulation: Hot Springs of the Yellowstone National Park, and Bore-Hole Investigations in Yellowstone Park.

When mineral-saturated hydrothermal waters rise from below the surface, silica precipitates in the form of silicon dioxide, creating the white material known as sinter that builds up along the periphery of geysers and pools.

Precipitation?

Only don’t ask your local weather forecaster about this kind of “precipitation.” Mineralogical precipitation is when a mineral forms by crystallization from a solution (think salt, precipitating from a saline-rich lake when water evaporates). Groundwater forced up by geysers is naturally rich in dissolved minerals.

Photo Jeff Having, University of Minnesota, Aug 2022, USGS/Public Domain

“The attractive visual display of colors observed in Yellowstone’s geothermal waters reflects an interplay of physical, chemical, and biological phenomena. Geothermal waters in the earth’s subsurface boil with steam separation and mix with dilute ground waters (that may or may not contain sulfuric acid from sulfur oxidation), resulting in a range of compositions when they discharge and emerge at the surface,” observed D. Kirk Nordstrom, hydrogeochemist emeritus with the Volcano Research Center, and research chemist R. Blaine McCleskey, while studying ground-to-surface water and the chemistry of thermal outflows at Yellowstone in 2005.

Also known as siliceous sinter, or geyserite, the lightweight opalescent deposits (called breccia) left on the surface break down naturally under the hooves of bison or during freeze-thaw cycles; however the traipsing of tourists along the edge of geyser basins or hot springs – even by former James Bond actors – is firmly discouraged and enforced.

USGS/Public Domain

The Sinter Cycle

“It’s a common misconception that all geysers and hot springs in Yellowstone are acidic,” wrote Pat Shanks, research geologist emeritus with USGS, for an August 16, 2020 issue of Caldera Chronicles.

It’s not difficult to see how Yellowstone earned dual descriptions from early explorers as both a wonderland and hell on earth. The National Park Service estimates at least 22 people have succumbed to burns received in its springs or geysers, including the unfortunate Colin Nathaniel Scott, believed to have dissolved after leaving the boardwalk at Norris Geyser Basin to find a place to soak, and Il Hun Ro, whose only mortal remains, after apparently falling into Abyss Pool, were a single foot found floating in its thermal waters by a park service employee.

Acidic? Sure Sounds Like It

“Some are, but the water that comes out of many of Yellowstone’s most iconic features, like Old Faithful and Grand Prismatic Spring, are actually basic,” Shanks noted. Natural water can be acidic, neutral, or alkaline (“basic”).

Yellowstone’s hydrothermal system is the result of interaction between rainwater and snowmelt, high temperatures beneath the ground, magmatic gases and the geology of the rocks making up its subsurface.

Citing a park-wide study from 1935, geyser and hot spring waters are commonly alkaline, and contain dissolved silica that precipitates during surface cooling, resulting in the layered white sinter terraces found around many Yellowstone geyser basins. Two competing processes control pH: Entrainment (making something part of a flow) of acidic magmatic gases like carbon dioxide, and a hydrothermal reaction with silicate rocks, which causes fluids to become alkaline.

“The take-home lesson,” Shanks surmised, “is that a reaction with rocks in the subsurface exerts a powerful control on the pH of fluids in Yellowstone geysers and hot springs. While some hydrothermal areas are indeed acidic, like those involving mud pots and steam-driven fumaroles, many of the geysers and hot springs we know and love have a basic pH.”

Photo James St John, Creative Commons Share Alike/Wikipedia

Geyser Eggs

Not all siliceous sinter results in terraced slopes like those around Old Faithful. Siliceous pebbles, or “geyser eggs” are products of alkali chloride hot pools.

“Geyser eggs don’t spawn a swarm of baby steam-sputtering structures. They are, after all rocks, but they’re far from ordinary,” said GeologyIn.com, comparing the pebbles to the geologic equivalent of candy jawbreakers while referring to a 2018 study on geyser eggs and sinter done on an Old Faithful sample.

Such bean-shaped pebbles, roughly the size of a silver dollar, are not dissimilar in appearance from a western state evaporite known as barite crystal or “desert rose,” and making eggs is not unlike making candy: When heated sugar water is cooled, it crystallizes into hard candy. Geyser eggs cool and solidify too. Layer by layer, silica from the steamy waters of geothermal precipitate takes a snapshot of pool conditions.

For the 2018 study, one smooth oval geyser egg, roughly 35 mm long x 18 mm wide x 26 mm high, was sampled from the slope of Old Faithful. It was cut in half to examine its genesis, sinter architecture and elemental composition reported Bridget Y. Lynne of the University of Auckland, one of the co-authors of ‘The formation of geyser eggs at Old Faithful Geyser,’ published September 2018 in Volume 75 of Geothermics.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

The multi-technique approach included Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), an iTRAZ Core Scanner, and Computerized Tomography (CT) scans revealing “alternating smooth and porous concentric bands of opal-A silica around a nucleus. Opal-A silica entombs pollen, diatoms, plants, lithic fragments, older sinter surfaces and microbes that thrive in hydrothermal water. The distinct pattern of alternating filamentous and non-filamentous horizons suggests a cyclic pattern of changing hot pool conditions.”

The CT scans showed concentric banding of varying density around a core (unlike tree rings, its layers do not appear to be annual). The SEM showed an abiotic origin, and iTRAZ scans revealed changes in fluid chemistry, a core rich in arsenic and calcium, and higher concentrations of gallium compared to prior samples.

“This was the largest collection of the rare rocks that I have seen in my scientific career. For me, this added a new dimension to the iconic status of the Old Faithful geyser,” Lynne said. “It is amazing to think that these little rocks are ‘actively recording’ and preserving the history of discharging fluid for as long as it is growing.

“Unraveling geyser egg formation mechanisms and their microbial content provide insights in fluid chemistry, water temperature, and flow conditions in these unique hot spring environments.”

Rumblings From Below

Analyzing sinter and geyser eggs from Yellowstone can help us better understand the messages rumbling up from our earth.

They may even, posits University of Alberta geologist Brian Jones (who was not involved in the 2018 study), hold the secret to early life as geysers were home to some of our earliest cellular forms.

Cracking geyser egg samples may one day crack the code to our own microbial beginnings, turning a trip to Yellowstone from a field trip into a homecoming.

Hello, Old Faithful.

Plan Your Trip To YellowstoneYellowstone is our nation’s first (1872) national park. While collecting, rock hounding and gold panning rocks, minerals and fossils – for recreational or educational purposes – is generally prohibited, this iconic destination is not to be missed. Peak season is June, July and August so if you want to avoid crowds, best to visit in April, September, or October. |

This article about sinter geyser eggs at Yellowstone previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by L.A Sokolowski.