Stalactite mineral specimens are different than common cave formations. These are lovely, usually very delicate slender stalactites of collector minerals and present a rather limited type of mineral collecting. This type of collecting can be challenging to a collector’s tenacity to maintain the search for fine examples of such odd specimens. After all, how often do you see a really nice, undamaged mineral stalactite?

The very nature of such a physical form lends itself to easy damage when you are collecting in a mineral pocket. Any long, slender mineral protrusion hanging from the roof of a mineral pocket would, by its very structure, easily suffer damage.

How are Mineral Stalactites Formed?

Like the sturdy stalactites we see in limestone caves, mineral stalactites form from dripping waters, except these waters are loaded with a mineral other than calcite, the normal cave stalactite mineral.

Museum exhibits often have few if any specimens in a nice stalactite form. The exception to that is exhibits of calcite limestone stalactites as a representative cave. But these are designed to show how cave formations develop, not to show off a variety of species in unusual forms.

Chrysocolla Stalactite Specimens

In 1997, mining in the huge open pit at Ray East of Phoenix, collectors were treated to the discovery of a huge quantity of chrysocolla stalactite specimens. They were encountered in the still-active Pearl Handle Pit, where mining exposed a large open seam crowded with blue to blue-green specimens of chrysocolla.

Instead of the usual solid chrysocolla-filled seam, this exposure was a large pocket arrangement where long, thick, sometimes curving fingers of chrysocolla from the copper-rich descending solutions had developed. There were quantities of tight clusters, sometimes with as many as a dozen or so thick fingers of the copper silicate in tight sub-parallel groupings hanging like stalactites.

The size of these growths ranged from pencil-thin to thicker than your thumb to the base. They measured from a couple of inches long to 10 inches long and were single growths or clusters of a dozen or more co-joined stalactites. Most tapered from a solid base, sometimes greater than an inch across to a near termination width of a quarter-inch. Most of the chrysocolla stalactites were smooth but usually undulating surfaced showing growth patterns as the shaft of the stalactite varied slightly in thickness, suggesting changes in the solution richness.

Chrysocolla Stalactites – Features

An odd feature in these chrysocolla stalactites is that many of them were curved. When stalactites develop, they are under the influence of gravity and tend to develop straight down. But sometimes an outside influence like air currents or even the direction of flow of the invading solution can cause a curvature or thickening on one side of the stalactite that can influence the overall shape. The chrysocolla stalactites from Ray, Arizona, are very attractive, quite unusual, and different from most stalactites.

Chrysocolla is an amorphous mineral, only crystallizing in microscopic crystals. One feature of these chrysocolla stalactites is that their core is not some other mineral as happens when goethite serves as the basis for stalactitic growth. Most mineral stalactites start out with a goethite or other mineral core, on which the other species develop.

Growth From the Exterior

On the broken ends of a stalactite from here, you might expect to see a tiny opening down the center of the specimen, forming a small opening or tube down which fluids could drip and from which the outward growth of the stalactite develops. When such straw-like openings did not exist, the stalactite had to have grown as waters dripped down the exterior of the stalactite, suggesting the growth occurred externally. As long as fluids continued down the outside of the stalactite, it would grow thicker and thicker. This might suggest that the undulating external form of the stalactite could be related to seasonal wet-dry periods.

Quartz Crystals

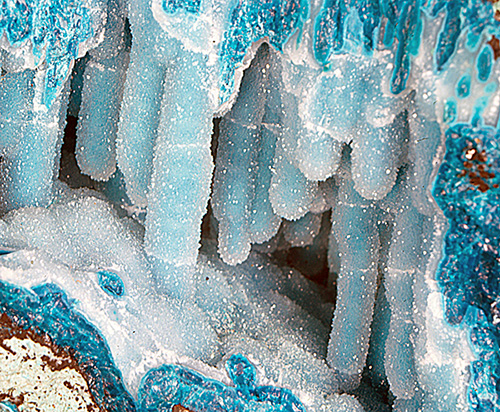

What makes some of these Ray mine chrysocolla stalactites special is that later silica-rich solutions got into some of the stalactite pockets and areas, and bright, sparkling quartz crystal points formed on the earlier formed chrysocolla stalactites.

The quartz points completely cover the stalactites and are often microscopic but brilliant and transparent. The image of the blue chrysocolla stalactite is seen through the sparkling crystallized quartz covering.

As exciting as this find was, the important thing to point out here is that the company realized they had an important find. They hired an experienced miner-specimen digger, Andy Clark, to collect all the specimens and arrange them in lots for sale, and auctions were held for local collectors and dealers to bid. This was a win-win situation. The company made money and collectors got wonderful specimens that would otherwise have gone to the crusher.

Common Stalactite Mineral Forms

One of the most common stalactite mineral forms seen as slender stalactites is goethite. This hydrous iron oxide seems to have a penchant for forming stalactites where space allows. Goethite is a secondary mineral and is easily formed from solutions descending into open cavities in a deposit. The goethite may form stalactites that are not part of the original pocket solution. Such hanging protrusions can offer points of attachment for minerals in later invading solutions that enter the pocket.

When a point of attachment is available, a mineral that is dissolved in a later invading solution may start crystal growth in the right conditions, and the goethite stalactite suddenly is decorated with another mineral species.

Morenci Stalactite Pockets

In Arizona, there have been some major finds of stalactite minerals that have produced spectacular specimens. One of the more spectacular stalactite pocket discoveries happened at the Morenci copper mine in 1986. Fortunately, the company was smart enough to have issued specimen-collecting contracts earlier, so when blasting and mining opened any crystal veins or pockets, the specimen-collecting team would be notified. As long as collecting did not interfere with mining operations, specimens could be retrieved.

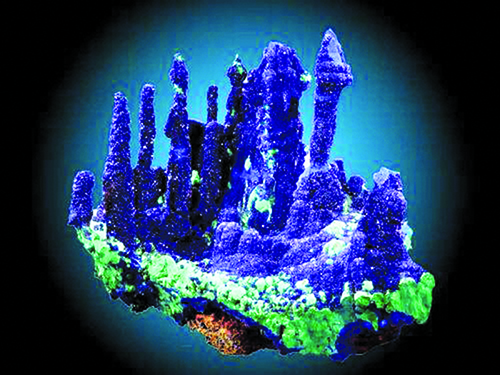

In that year, a large series of pockets of azurite had been opened and were made available for collecting. The pockets were full of goethite stalactites on which countless small, brilliant blue azurite crystals had developed along the entire length of each stalactite. Some stalactites were covered with blue crystals. Others had a smattering of such crystals. All were stunningly beautiful!

The initial excitement in seeing such a find was quickly tempered when diggers realized that most of the stalactites had cleaved or broken off the matrix and lay scattered in the pockets.

Collecting Everything!

The Morenci stalactite pockets were found when the company decided to mine an old oxide area left dormant for years. Mining resumed in 1986 and the stalactite pockets would have been destroyed except the company had agreed to a specimen collecting arrangement so when crystals were encountered they could be collected and saved.

When the collecting group went to work extracting the entire pocket lining from which the stalactites were first mined, they also collected every one of the broken stalactites in hopes of reattaching them to the pocket matrix that was also collected. Then the fun really began!

Over many months, the basic matrix pieces were examined, and the broken azurite bases on each stalactite were examined in hopes of matching the azurite-covered stalactites to where they had originally formed. Luckily, the cleaved stalactites were near-perfect, and finger after finger was fitted back where it belonged, returning each stalactite to its original place on the specimen. The result was a spectacular specimen after it was assembled to its original form of goethite decorated with very lovely blue azurite crystals. These very showy and quite rare specimens were snapped up by collectors as soon as they were marketed. But that’s not the end of the story.

Morocco Stalactites

Another source of stalactites is Morocco. The vanadinite mines of Mibladen have yielded long, slender goethite fingers beautifully decorated with bright red, sharp vanadinite crystals. These are quite rare but very appealing when found, as they are exceptional and uncommon, to say the least.

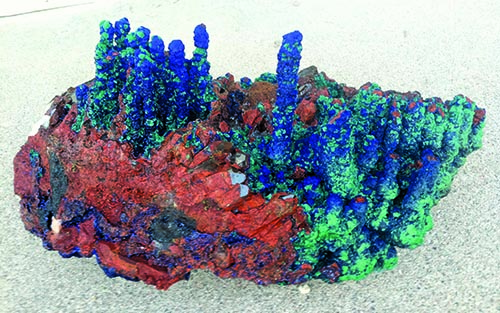

Morocco has also produced azurite-malachite stalactites, somewhat like the Morenci specimens. They are attractive and colorful. The stalactites with their azurite decorations are shorter than the Morenci fingers, seldom over a couple of inches high.

Malachite Stalactites

Malachite is another mineral that forms stalactites. It is a secondary mineral, so solutions can drip into openings in copper deposits, bringing with them malachite. The huge deposits at Zaire have yielded large quantities of such specimens, some of them quite spectacular. This source has undoubtedly produced a greater number of stalactite-type specimens than any other deposit.

Stalactite specimens are not common. By their very nature of formation, they are limited – and by their fragile nature even more so. This suggests that if you see a good stalactite specimen, pick it up. It adds yet another dimension to your collection.

This post about stalactite mineral specimens previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Bob Jones.