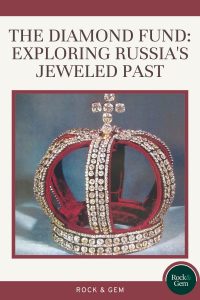

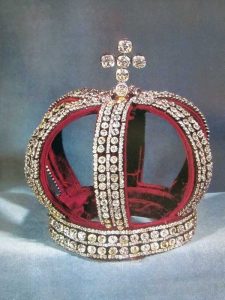

The Diamond Fund public exhibit is one of Russia’s most popular visitor attractions in Moscow’s Kremlin Armoury. The highlight of this exhibit is the Great Imperial Crown, which gleams with 4,936 diamonds, 74 large pearls, and a 398.6-carat red spinel. This 260-year-old royal crown is the preeminent symbol of the splendor and elegance—and some say, the excess—of imperial Russia’s Romanov Dynasty.

As part of Russia’s Ministry of Finance, the Diamond Fund was established more than 300 years ago during the reign of Peter the Great. Today, it maintains one of the world’s great gem collections. Its story is an epic of gemological triumph, personal tragedy, political upheaval and, ultimately, preservation and renewed growth.

After imperial Russia ended abruptly with the 1917 Russian Revolutions, the Diamond Fund endured two decades of chaos, theft, mismanagement, and liquidation. But the Fund’s fortunes have since improved markedly; its collection now includes many of Russia’s original crown jewels and coronation regalia, some of the world’s most historic gems, elaborate Romanov jewelry, and spectacular diamonds from modern Russia’s mines.

The Diamond Fund – Humble Beginnings

The concept of crown jewels—gemstone studded crowns, scepters, and orbs—as symbols of royal wealth, power, and authority had become well-established among western European royalty by 1000 CE. But the first Russian royal regalia— simple golden caps and broad neckpieces called barmas—didn’t appear until the 1200s.

Russia’s first crown was Monomakh’s Cap, also known as the “Golden Cap.” This gold-filigree skullcap was sparsely adorned with rubies, emeralds, pearls, and topped by a golden cross. Enclosed in a circlet of sable, it clearly has a Central-Asian style.

By the time of Mikhail Romanov (Michael I, reigned 1613-1645), the first tsar of the long-lived Romanov Dynasty, Russian regalia had become increasingly elaborate with greater emphasis on gemstones, especially diamonds. The silk barma of Alexei Michailovich (Alexis of Russia, reigned 1645-1676) featured seven enameled medallions, 249 diamonds, and 255 colored gems; his orb glittered with 179 diamonds and 340 colored stones, his scepter with 268 diamonds and 360 colored stones.

Russia’s early tsars also amassed family gem collections. Alexei’s personal, six-foot-long staff was set with 178 diamonds, 259 emeralds, 3 large pearls, and 369 pink tourmalines; his personal throne, fashioned of ivory, was studded with 876 diamonds and 1,223 colored stones.

Peter the Great (Peter I, reigned 1682-1725) expanded the Russian empire and developed it into a major power. In 1719, Peter ordered the Romanov jewels to be kept separate from the state jewels, and that the latter be secured in a repository that became known as the “Diamond Room”—the forerunner of today’s Diamond Fund. He also mandated that the state jewels never be sold and that future tsars and tsarinas would contribute a portion of their personal gem collections to the Diamond Room collection.

A Change in Style

The style of Russian crowns changed in the 1700s, when design and manufacture shifted from jewelers in Constantinople (today’s Istanbul) to those in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Unlike the earlier golden skullcaps, the crown of Catherine I (reigned 1725-1727), set with 2,000 diamonds and a large pink tourmaline, copied the arched style of western European crowns.

The crown of Anna Ioannovna (Anna of Russia, reigned 1730-1740) featured two open-work hemispheres divided by an arc and topped by a cross; it was set with 2,536 diamonds, 28 colored gems, and 500-carat, a red, Chinese tourmaline.

Catherine II (Catherine the Great, reigned 1762- 1796) ruled during Russia’s Golden Age when art, music, theatre, and literature flourished. Catherine II’s fondness for gems is reflected in the Great Imperial Crown made for her coronation and now the centerpiece of the Diamond Fund’s public exhibit.

At the time, this crown’s 398.6-carat spinel, an irregular, partially faceted stone, was thought to be a ruby. It is similar in shape to, but much larger than, the well-known “Black Prince’s Ruby” (a 170-carat red spinel) in the British Crown Jewels collection. The confusion between red gems was largely resolved in 1783 when mineralogists learned to differentiate between true ruby (corundum, aluminum oxide) and spinel (magnesium aluminum oxide).

Catherine the Great also loved amethyst, which was then much more valuable than it is today. She ordered prospectors into the Ural Mountains to search for amethyst sources, which they discovered, but only after Catherine’s death in 1796. Prospectors in the Urals later found deposits of emeralds, demantoid (garnet, the green gem variety of almandine), and alexandrite. The latter, the color-change variety of chrysoberyl (beryllium aluminum oxide) was named for Tsar Alexander II (reigned 1818-1881).

By the 1800s, the state’s crown jewels included many large stones of great historical significance; the Romanov collection of gems and jewelry featured huge numbers of high-quality diamonds that came mostly from the historic mines near Golconda, India, with smaller amounts from Brazil. Although South African diamonds became available in the late 1800s, they seemed to attract little Romanov attention.

A Revolution

The final chapter of the Romanov Dynasty was written under the rule of Nikolay Aleksandrovich Romanov (Nicholas II, reigned 1894-1917), a politically inept leader who presided over a difficult period of political and social unrest. Only after World War I had pushed Russia to its social, fiscal, military, and political limits, and tore the nation apart, did the world learn the extent of the gemological treasures that the state and the Romanovs had acquired over the previous two centuries.

After the February Revolution of 1917 deposed Nicholas II, a provisional government placed the Romanovs—Nicholas, his wife Empress Alexandra, and their five children—under house arrest ostensibly for its safety, the family was exiled to Tobolsk in the Urals. The Romanovs took with them personal belongings that included a fortune in gems and jewelry.

In the October Revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks ousted the provisional government and triggered a civil war. The following April the Bolsheviks confiscated the Romanovs’ belongings and moved the family to Yekaterinburg. Before leaving Tobolsk, the Romanovs hid their bulky diamond jewelry in a convent. For their financial security in hoped-for foreign exile, they sewed a fortune in loose diamonds into their daughters’ corsets and other clothing.

As an anti-Bolshevik militia neared Yekaterinburg on July 16, 1918, the Bolsheviks shot the entire Romanov family in a brutal, clumsy execution. When the daughters’ diamond-filled corsets deflected bullets, the execution was completed with bayonets. While disposing of the bodies, the Bolsheviks found 41,000 carats (18 pounds) of diamonds in the garments of the victims.

Protecting the Past

Bolshevik leaders then began debating the fate of what was collectively called the “Russian treasure”—the state’s crown jewels and regalia, along with the seized gems of the Romanovs, their extended family, and former aristocrats. The Bolshevik’s choices were either to sell the treasure abroad for desperately needed hard currency or to preserve at least part of it for its historical value.

But with no inventory and poor security, the jewels quickly began disappearing. In 1919, American customs agents in New York City detained several Russians surreptitiously carrying, and admittedly intending to sell, part of the Russian treasure.

In 1920, Bolshevik leaders established the Diamond Fund, which was similar to the original Diamond Room, as a secure repository for the jewels. The following year, they appointed a 63-member committee to inventory and appraise the treasure. But when theft was suspected, the entire committee was brought before tribunals; 23 members were executed and many others were sent to labor camps.

Taking Inventory

Just before the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was founded in 1922, the People’s Commissariat of Finance appointed another appraisal committee, this one headed by the respected mineralogist and geochemist Alexandr Evgenevich Fersman. Fersman’s inventory listed 25,300 carats of diamonds, many in gems of five or more carats. Notable stones included a 46-carat blue diamond in an imperial orb; the 189.6-carat, slightly greenish Orlov Diamond in a scepter; and the historic, 88.6 carat Shah Diamond that dated to the 1500s.

Among the 3,200 carats of emeralds, most from Colombia, were many “large and very rare” gems like the spectacular, 136-carat Sinople Queen Emerald. Half the 2,600 carats of Kashmir, Siam, and Ceylon sapphires were “gems of great historical and scientific value.” Half the 1,300 carats of red spinel were stones of 50 or more carats. Other gems included “topazes, alexandrites, aquamarines, beryls, chrysolites, large turquoises, chrysoprases, smoked-topazes, fine amethysts and agates, Bohemian grenats [garnet, pyrope, garnet], labradores [labradorite], and almandines [garnet, almandine].”

The Diamond Fund – Jeweled Surprises

Surprisingly, the inventory listed a mere 200 carats of ruby. Fersman suspected that the tsars, while certainly capable of acquiring fine rubies, had a superstitious aversion to their blood-red color.

Fersman’s examination also revealed that the 398.6 carat “ruby” in Catherine II’s Great Imperial Crown was actually a spinel. This stone, acquired in China by a Russian envoy in the late 1600s, turned out to be the world’s second-largest gem spinel.

Another surprise concerned the historic “Caesar’s Ruby.” This 255.6-carat, raspberry-shaped “ruby,” a gift from Sweden to Catherine II in 1777, proved to be rubellite, the red variety of the tourmaline-group mineral elbaite.

The inventory listed very few amethysts, alexandrites, and Russian emeralds, which was surprising since these stones were regularly mined in the Urals. Fersman believed that the Romanovs had simply preferred foreign gems and had lavishly gifted most of the Russian stones to foreign dignitaries.

Precious Eggs

The inventory also included the jeweled eggs of Peter Carl Fabergé’s House of Fabergé, the jeweler to the crown. Between 1885 and 1916, Fabergé had made 51 jeweled, “imperial eggs” for the Romanovs. Among them was the “Lilies of the Valley,” an especially elaborate egg with enameled portraits of three Romanov family members. Made of pink enamel, gold, diamonds, and pearls, it had been a gift from Nicholas II to his wife Alexandra in 1898.

In 1922, the value of the Russian treasure was estimated at four million rubles (more than $1 billion in 2021 dollars). The intent to convert at least some of the treasure into hard currency was apparent in the appraisal committee’s final report, Russia’s Treasure of Diamonds and Precious Stones. Published in 1925 in catalog form in German, French, and English, it was clearly a prospectus aimed at enticing foreign gem buyers.

Up for Sale

In 1927, the Soviets approved a major sale of the Russian treasure—154 lots of gems, jewelry, and regalia that were sold at a London auction. These items included some of Catherine the Great’s jewelry; an 1884 diadem with 1,375 diamonds, including a rare, 13-carat pink stone; and the 1840 Russian Nuptial Crown set with 1,535 diamonds. The Soviets justified the sale by deeming these objects to be of “little historical importance.”

But even as some jewels were being sold, others were turning up. In 1933, Soviet investigators tracked down the Romanov jewelry that had been hidden in the Tobolsk convent in 1918. Among the 150 individual pieces recovered were two brooches, each set with more than 100 carats of diamonds.

The Soviet government continued to quietly sell the Russian treasure to private buyers until 1936. By then, more than half the original inventory of 1922 had been sold, misplaced, or stolen. But, fortunately, the remaining items included most of the historic Russian regalia, some of which dated to the 1300s.

Of the Romanovs’ 51 Fabergé imperial eggs, 41 were either lost or sold into private ownership; only 10 remain in the Diamond Fund today. The value of these imperial eggs became clear in 2004, when the “Lilies of the Valley” egg sold for $12 million to a private Russian museum. That same year, a Russian billionaire paid more than $100 million to acquire nine Fabergé imperial eggs from an American collector.

Although the state and the Romanovs had amassed huge numbers of diamonds, Russia itself had never been a diamond producer. But during the industrialization that followed World War II, the Soviets needed, but would ill afford, a steady supply of industrial diamonds. In 1946, confident that diamonds existed somewhere in Siberia, the Soviets launched an intensive exploration program.

Eight years later, Russian geologists discovered the Zarnitsa and Mir diamond-bearing kimberlite pipes. By the 1960s, the Mir open pit was producing 10 million carats of diamonds per year—a remarkably high 20 percent of which were gem quality. Over its 40-year life, the Mir pit yielded more than 100 million carats of diamonds and contributed $25 billion to the Soviet economy. Today, as the world’s leading diamond producer, Russia mines six kimberlite pipes and recovers 43 million carats per year.

The Diamond Fund – Growing the Collection

Since Russia began mining its own diamonds, the Diamond Fund collection has grown substantially. Under state policy, the Fund acquires all Russian-mined raw diamonds larger than 50 carats and all faceted diamonds larger than 20 carats. Recent acquisitions include a 342.5-carat diamond from the Mir pit that was named, in inimitable Soviet-style, The 26th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Diamond; the 320.7-carat Alexander Pushkin Diamond, named for the celebrated Russian novelist and poet of the early 1800s; and the 298.48-carat Creator Diamond.

The Diamond Fund collection also includes Russian gold nuggets, among them a 36.2-kilogram (80-pound) specimen found in 1840 and a 33-kilogram (73-pound) nugget mined in 2003, both from the Urals.

Showing Off

The Diamond Fund collection had remained securely locked out of sight in the Kremlin Armory until a temporary public exhibition was held in 1967 to mark the 50th anniversary of the Russian Revolution. Because of great public interest, the exhibit became permanent the following year. The value of Diamond Fund’s collection was then estimated at more than $7 billion. In 2012, to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the Great Imperial Crown, the Diamond Fund fashioned a modern replica. Made of white gold at a cost of $15.5 million, this replica glitters with 11,426 diamonds, 74 large natural pearls, and a 398-carat, purplish-red, irregular red tourmaline.

With the irreplaceable, original Great Imperial Crown too valuable to leave the Kremlin, its replica is part of traveling exhibits inside and outside of Russia. Also, because mounted gems are worth much more than loose stones, the value of the thousands of diamonds in the replica has substantially increased. And that’s important, because the Diamond Fund collection, currently valued in excess of $50 billion, partially backs the Russian ruble.

The Russian Diamond Fund story is one of gemological triumph in amassing world-class collections, tragedy in their seizure and sell-off, and triumph again in their partial preservation and renewed growth.

For fascinating reading, Aleksandr Evgenevich Fersman’s 1925 committee report on Russia’s Treasure of Diamonds and Precious Stones is accessible in its entirety online.

This story about the Russian Diamond Fund previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.