By Steve Voynick

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a two-part series exploring the evolution of gold mining in Colorado. Read Part II >>>

Colorado has been mining gold even before the region became a territory and is still mining it today. In fact, some of Colorado’s newly mined gold was refined to .9999 purity and milled into 140,000 sheets of gold leaf just 1/8000th of a millimeter thick to regild the 250-foot-tall dome of the state capital building in Denver.

When Colorado’s capital was built in 1898, the dome was clad in copper. But in 1908, to mark the 50th anniversary of the Pikes Peak gold rush, the state fathers ordered the dome gilded with gold. Mine owners at the then-booming gold camp of Cripple Creek donated the required 200 troy ounces of gold. Cripple Creek miners also provided the gold for the recent regilding of the dome. However, this time, it took only 65 troy ounces, thanks to the ability to create an ever-thinner gold leaf. Another sign of changing times is the price of the gold itself: The 200 troy ounces needed to gild the dome in 1908 cost $4,000; today, the necessary 65 troy ounces cost $127,000.

Speaking at the completion of the regilding project, former Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper called gold “a true Colorado treasure that symbolizes its past, present, and future.” Indeed, Colorado opened with a gold rush; today, it still produces 300,000 troy ounces of gold each year. As for its future, the former governor and now U.S. senator, a geologist himself, referred to the ability to economically extract gold from very low-grade ores that will enable Colorado to produce gold for decades to come.

Colorado’s historic gold production is now nearing 53 million troy ounces. That amounts to 1,648 metric tons, which would occupy a 14-foot cube and be worth $100 billion at today’s gold prices.

Humble Beginnings

A French trapper made the first reference to Colorado gold in 1758 when he wrote of a rivulet, possibly a tributary of the upper Arkansas River, “whose waters rolled down gold dust.” Over the next century, a dozen other reports told of gold in the same general region. Oddly enough, the first historically significant discovery, made in 1858 near the South Platte River in what is now southwest Denver, actually yielded very little gold. Nevertheless, a sack of gold-bearing gravel (doubtlessly concentrated) was brought to Westport (now Kansas City, Missouri) and panned before a wide-eyed audience.

Newspapers and promoters heralded the strike as the “next California” and, by spring of 1859, some 100,000 gold seekers had rushed to “Pikes Peak Country,” where they found not gold but only bitter disappointment. As many of these “fifty-niners” began heading back east, the Pikes Peak gold rush seemed destined to become one of the West’s bigger fiascos. But a handful of more determined prospectors headed the opposite way—west into the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, where they quickly made two major strikes that redeemed the rush at its darkest moment.

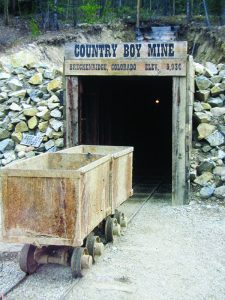

The first strike was on the North Fork of Clear Creek near the present-day towns of Black Hawk and Central City; the second was on the South Fork at the future site of Idaho Springs. By summer, a dozen booming, placer-gold camps dotted the foothills just 25 miles west of Denver. Prospectors then panned their way west, making discoveries at Breckenridge, Alma, Tarryall, and Fairplay. By autumn, they had struck gold at California Gulch near today’s Leadville. In just five years, California Gulch, the richest strike of the entire Pikes Peak rush, yielded 300,000 troy ounces of gold worth nearly $5 million.

By 1870, when the rich discovery gravels had been largely depleted, the fifty-niners had panned and sluiced 1.3 million troy ounces of gold worth $25 million. In the process, they settled a wilderness, created a territory, and set the stage for far richer gold strikes. The search for gold has enriched Colorado’s history with wonderful tales of sudden wealth and, in some cases, of the heartbreaking loss of wealth.

Colorado’s Early Mining Legends

In 1878, Breckenridge miner Harry Farncomb found a rich, eluvial gold deposit in intricately twisted wires and delicate leaves. Farncomb quietly mined his find alone while buying the adjacent properties. Two years later, he revealed his discovery by depositing hundreds of troy ounces of beautiful, crystallized gold in a Denver bank, then sold his property, now known as Farncomb Hill, for a fortune.

In 1887, two miners leased a section of Farncomb Hill and recovered a 10-pound mass of crystallized gold. Named “Tom’s Baby,” it is still the largest single piece of gold ever found in Colorado. Farncomb Hill’s crystallized gold had a profound effect on the collecting and value of gold specimens. Because of its rarity and beautiful shapes, the specimen value of Farncomb Hill gold far exceeded its bullion value. In 1900, one of the founding gifts to the Denver Museum of Natural History (now the Denver Museum of Nature & Science) was a spectacular, 600-piece collection of gold from Farncomb Hill.

In southwestern Colorado’s San Juan Mountains, gold mining was delayed because of both Ute hostility and the lack of rich, easily mined placer deposits. Nevertheless, prospectors eventually found many lode deposits and, by the 1880s, camps like Telluride, Silverton, and Ouray had dozens of underground gold-silver-lead mines. The greatest rags-to-riches story in the San Juan Mountains was that of Thomas Walsh. Unlike most prospectors, Walsh did not search for new mineral deposits; instead, he assayed samples collected at abandoned mines. In 1896, he found gold-laced quartz in a mine dump near Ouray and traced it to an exposed vein that previous miners had somehow overlooked. That three-foot-wide vein contained 150 troy ounces of gold per ton.

Walsh bought the abandoned mine for a pittance. Then, backed by his phenomenal assay reports and uncontested ownership of the mine, he borrowed development capital. In just five years, his Camp Bird Mine, the richest American gold mine ever owned by a single individual, had yielded 200,000 troy ounces of gold and a clear profit of $2.4 million. Walsh then sold out for $6 million in cash, stock, and future royalties. His daughter Evalyn, the heiress to the Camp Bird fortune, later gained international notoriety as a socialite who purchased the Hope Diamond.

If you enjoyed what you’ve read here we invite you to consider signing up for the FREE Rock & Gem weekly newsletter. Learn more>>>

In addition, we invite you to consider subscribing to Rock & Gem magazine. The cost for a one-year U.S. subscription (12 issues) is $29.95. Learn more >>>