By Steve Voynick

Editor’s Note: This is the second in a two-part series exploring the evolution of gold mining in Colorado. Read Part I >>>

By 1890, Colorado produced a quarter-million troy ounces of gold annually, a figure that would soon quadruple, thanks to an itinerant cowboy and part-time prospector named Bob Womack. In 1892, high on the western side of Pikes Peak at a lonely cow camp called Cripple Creek, Womack found gold-bearing rock that graded 12 troy ounces to the ton. But unlike Thomas Walsh, Womack did not go from rags to riches. Not knowing the actual extent of his discovery, he sold out for $300—only to learn later that he had found one of North America’s richest gold deposits. Production at Cripple Creek peaked in 1900 when 475 mines turned out 900,000 troy ounces—28 metric tons—worth $18 million. That year, Cripple Creek produced two-thirds of all the gold mined in the United States.

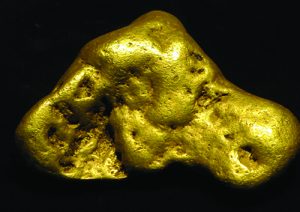

Cripple Creek gold occurred in elemental form and as the telluride minerals calaverite and sylvanite. Ores grading several hundred troy ounces of gold per ton were surprisingly common. Some ores were actually graded in dollars per pound, rather than the traditional troy ounces per ton.

In 1914, miners at Cripple Creek’s Cresson Mine blasted into a large vug 20 feet long, 15 feet wide, and 40 feet high that was lined with crystallized gold. Under the watchful eyes of armed guards, miners worked for a month to clean out what was named the “Cresson Vug.” Miners filled 1,400 sacks with gold flakes worth $400,000, then filled another 1,000 sacks with lower-grade material worth $100,000. Finally, they blasted and sacked the gold-laced rock in the vug wall. The Cresson Vug yielded 60,000 troy ounces of gold—nearly two metric tons—worth over one million dollars.

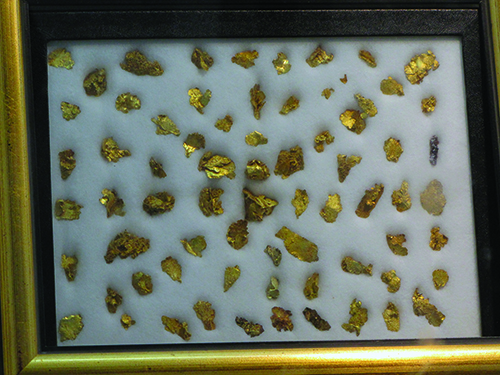

Because the native gold and gold tellurides in the Cripple Creek ores were often visible, many miners succumbed to the temptation to “high-grade” or steal the ore. Mine owners did everything possible to prevent high-grading, but the miners found creative ways to spirit gold out of the underground. Historians conservatively estimate that over 25 years, Cripple Creek miners high-graded one million troy ounces of gold worth nearly $20 million.

Growth By Way of Innovative Technology

By 1900, depletion of shallow placer gravels had made traditional sluicing only marginally profitable. Although much gold remained in the deep gravels, there was no economical way to mine it—until the introduction of the floating, bucket-line dredge. Steam-powered, floating dredges, developed in New Zealand in 1890, appeared in Breckenridge in 1898. Although notoriously inefficient, they were well-suited to work the deep gravels of the local rivers. When the dredges were converted from steam to electrical power in 1905, they became quite profitable.

The bucket-line dredges operated in several Colorado placer districts, but most extensively at Breckenridge. By 1916, the so-called “Breckenridge navy” consisted of six, 250-foot-long, bucket-line dredges and several smaller dredges. This dredge fleet operated until 1942, when it was put out of business by wartime restrictions on gold mining. The dredges had recovered 750,000 troy ounces of gold by then, making Breckenridge the all-time leading placer-mining district in Colorado.

Prospectors even found a few lode bonanzas after 1900. One was in the San Juan Mountains of Summitville, North America’s highest gold camp at an elevation of 11,300 feet. Following the boom-bust pattern of many other Colorado gold camps, Summitville opened with a rich strike in 1873 but in 20 years became a ghost town. In 1908, Jack Pickens, one of the district’s few remaining miners, found a fabulously rich piece of float in a talus slope and traced it uphill to a partially exposed vein of gleaming “picture rock” that earlier miners had missed. But the property was claimed, and Pickens could not obtain a lease.

Pickens told no one of his find for 18 long years. Finally, in 1926, he managed to lease the property and begin mining. His long wait was well worth it. Although the vein was small, the average ore grade was 28 troy ounces of gold per ton, but the vein’s narrow center section graded 230 troy ounces per ton. In just three years of small-scale mining, Pickens recovered a half-million dollars in gold.

The dollar values for gold mentioned thus far are based on a gold price of $20.67 per troy ounce. In the early 1930s, the United States and most other nations abandoned the gold monetary standard and revalued the metal. The new price, fixed at $35 per troy ounce in 1934, stimulated gold mining in Colorado and worldwide. The increased gold price coincided with the height of the Great Depression. With jobs hard to find, rusted gold pans and old sluices were put to work again on all of Colorado’s gold-bearing creeks and rivers. Many nearly abandoned gold-mining districts came back to life as miners increased production at operating gold mines, reopened many long-closed mines, and constructed new bucket-line dredges.

Gold mining even resumed along the South Platte River in Denver. To provide an income opportunity for the jobless, the city of Denver conducted free “gold-mining schools” in which experienced placer miners taught the largely forgotten arts of panning and sluicing. Thousands of out-of-work “students” participated, and the schools enabled their many “graduates” to pan or sluice a few dollars worth of gold every day—enough to put food on their tables. The renewed placer-mining activity also showed that the old-timers hadn’t found all the big nuggets. In 1937, high on Pennsylvania Mountain near Fairplay, miners recovered an 11.95-troy-ounce nugget. Named the “Penn Hill nugget,” it is the largest-known Colorado placer nugget ever found.

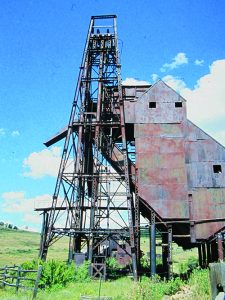

After World War II, inflation quickly caught up with $35 gold, and most of Colorado’s gold deposits were no longer worth mining. But the future of gold mining, not only in Colorado but worldwide, was already on the drawing boards in Cripple Creek. The Golden Cycle Corporation, the only surviving Cripple Creek mining company left from the boom days, constructed the Carlton Mill in 1950 to conventionally process the district’s few remaining ores. Like many districts, Cripple Creek had enormous quantities of gold mineralization left in the ground that was far too low in grade to mine profitably.

When a United States Bureau of Mines research team needed a place to test an experimental cyanidation-recovery process, Golden Cycle generously donated an unused corner of its Carlton Mill. Cyanidation, which uses cyanide solutions to dissolve metallic gold from ores, was nothing new. It had been introduced in the 1890s, but its use was limited because the only way to recover the dissolved gold was through costly and inefficient precipitation with powdered zinc. In 1951, the Bureau of Mines researchers at the Carlton Mill developed an inexpensive process to recover the dissolved gold from cyanide solutions by adsorption onto particles of activated charcoal and chemically desorp the gold in metallic form. By making mass cyanide leaching of very low-grade gold ores profitable, this process would revolutionize gold mining.

Modern-Day Mining Market

By the 1970s, when gold had become a free-market commodity and its price had soared, the cyanidation-charcoal-adsorption approach was adopted worldwide. In Colorado, mining engineers planned its first use at Summitville. But before the low-grade ores were mined, the old district had one last surprise. In 1976, a contractor working with exploration geologists noticed a boulder “with a streak of yellow” lying just off the shoulder of the district’s main gravel road. The 141-pound boulder consisted of a breccia of quartz latite fragments in a matrix of fine-grained quartz, barite—and gold. Its largest, visible gold vein was 12 inches long and a half-inch thick.

Now known as the “Summitville gold boulder,” the rock contained 350 troy ounces of gold with a bullion value of $50,000 (the gold price was then $142 per toy ounce). The company that had leased the Summitville property took possession of the boulder but later donated it to the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. For his trouble and honesty, the contractor who discovered and reported the boulder received a $21,000 finder’s fee from the company. The modern Summitville open-pit gold mine operated from 1985 to 1992 and produced 250,000 troy ounces of gold—before coming to an inglorious end when cyanide leaks polluted downstream drainages and created a federal Superfund site.

In Colorado, the cyanidation-charcoal-adsorption process had its most significant impact on Cripple Creek itself. In the 1980s, Golden Cycle Corporation, a partner in the Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mining Company, core-drilled the old mining district and delineated an enormous deposit grading only 0.027 troy ounces of gold per ton. The Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mining Company open-pit mine began production in 1995 and has just recently poured its six-millionth troy ounce of gold. The recovered gold is melted in electric furnaces and poured into cone-shaped, 70-pound “buttons” of doré, an 85-15 gold-silver alloy that is 98 percent pure. Each button contains 720 troy ounces of gold and is currently worth $1.4 million. Nine million tons of ore are mined, hauled, crushed, and leached to pour more than 400 buttons each year.

Although Cripple Creek is now Colorado’s only primary gold source, the state’s golden legacy has not been forgotten. Colorado gold is showcased at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, which displays many spectacular specimens of Farncomb Hill gold, along with Tom’s Baby, the Penn Hill nugget, and the Summitville gold boulder. In nearby Golden, the Colorado School of Mines library and Geology Museum also display fine specimens of Colorado gold.

Many of Colorado’s old gold-mining towns, including Idaho Springs, Central City, Black Hawk, Fairplay, and Cripple Creek, are within a two-hour drive of Denver. Most have local museums that display gold specimens and gold-mining artifacts, underground gold-mine tours, and other gold-related attractions. And gold panning and recreational dredging are popular summer activities on dozens of Colorado creeks and rivers.

Colorado’s gold-mining legacy now spans 160 years and is measured at five million troy ounces. Gold production continues at Cripple Creek, where Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mining Company geologists are delineating new ore bodies to extend the mine’s operating life. So it’s a good bet that newly mined Colorado gold will still be available in the future for the next regilding of the state capital dome.

If you enjoyed what you’ve read here we invite you to consider signing up for the FREE Rock & Gem weekly newsletter. Learn more>>>

In addition, we invite you to consider subscribing to Rock & Gem magazine. The cost for a one-year U.S. subscription (12 issues) is $29.95. Learn more >>>