By Steve Voynick

Many people, rockhounds and prospectors among them, rely on information from topographical maps, geological reports, and mining-district surveys.

Many also go on-line to check the magnitude of recent earthquakes, monitor current volcanic activity, or keep up with new developments in the Earth sciences. Much of this readily accessible, accurate information is compiled and made available by the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

More than A Century of Study

(USGS)

The USGS, familiarly known as the “Survey,” is the scientific agency of the U. S. Department of the Interior. When the Survey was established in 1879, much of the nation, especially the West, was unmapped and most of its mineral resources were yet undiscovered. Accordingly, the Survey’s initial work focused on mapping and mineral surveying.

The Survey’s interests have since broadened greatly with the advancement of science and the changing needs of the nation. Over 140 years, the USGS has presented the results of its field surveys and laboratory research in many thousands of reports, papers, and maps, making them available to the public free of charge or at a nominal cost.How all this information was compiled—and is still being compiled today—is a fascinating story.

In the early 1800s, the federal government had little interest in mapping and investigating the geology of its vast public lands.The few surveys of that era had been performed by the states or private interests, usually to support regional agricultural, military, or transportation projects.

Gold Rush Prompts Increased Interest

The California gold rush of 1849 inspired the first serious national interest in geology, mining, and mapping.Although the federal government established the Department of the Interior that year, geological and cartographic fieldwork remained limited to the Army Corp of Engineers’ search for transcontinental railroad routes.

The first dedicated geological surveys were undertaken by the states, notably California which, in 1860, demonstrated the economic benefits of surveys.As rapid depletion of the Mother Lode’s bonanza gravels made mining increasingly unproductive, the California Geological Survey ordered a statewide mineral survey specifically to revive the state’s mining industry.

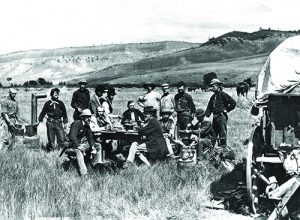

After the Civil War had ended, the federal government authorized and funded four geological surveys of the West.The first, an 1867 Army Corps of Engineers survey of the proposed 40th-parallel transcontinental railroad route, was headed by Clarence King, a 25-year-old Yale geologist, and veteran of the California Geological Survey.Leading the second survey, which investigated the resources of Nebraska and Wyoming, was former military surveyor Ferdinand V. Hayden, M.D.

The third survey sent John Wesley Powell, a Civil War veteran and professor of geology at Illinois State Normal University, into the southwestern canyon lands, an expedition that involved a harrowing, wooden-boat journey through the Grand Canyon.Army engineer George Wheeler led the fourth federal survey into Nevada and the Great Basin country.

Competition Impacts Surveys

All four surveys were successful and extended into the 1870s. But

competition and poor coordination created rivalry and duplication of effort. In 1878, Congress asked the National Academy of Sciences to suggest ways to effectively, yet inexpensively, survey and map the western territories. The academy recommended establishing an independent agency within the Department of the Interior with the mission of “classifying the public lands, and examining the geological structure, mineral resources, and products of the national domain.”

Congress concurred and, on March 3, 1879, President Rutherford B. Hayes signed a bill discontinuing all previous surveys and establishing the United States Geological Survey with initial funding to begin July 1. Based on his overall surveying experience and broad congressional support, Ferdinand Hayden was the logical choice to direct the new agency.

But an influential group of wealthy San Francisco mining magnates thought differently.A few years earlier, Clarence King had exposed the infamous “Great Diamond Hoax,” a scheme in which two con men salted ground in southwestern Wyoming with second-rate precious gemstones. Some of San Francisco’s most prominent citizens took the bait and invested, but were fortunate in avoiding further financial loss and public embarrassment when King personally visited the site and revealed it as a fraud.Because many of the duped San Francisco investors were personal friends and political allies of President Hayes, it was Clarence King who became the first USGS director.

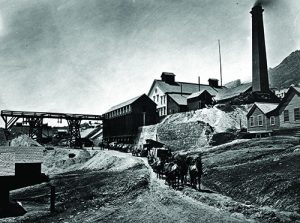

The USGS began work with 38 employees, a $106,000 annual budget, and considerable controversy.The agency’s critics, questioning the federal government’s involvement in science, demanded that the USGS direct its efforts toward immediate economic benefit, in other words, mining.Initially, the Survey focused on topographical mapping and compiling and publishing mining and mineral-resource statistics.But the politically astute King also ordered comprehensive field surveys of three great mining districts: Colorado’s Leadville district and Nevada’s Comstock and Eureka districts.

Kunz’s Work Sheds Light on Geology

The USGS was mandated to publish and make available for public sale and scientific exchange 3,000 copies of every report. Its first major publication was the annual Mineral Resources of 1882, a book-length account of the nation’s known mineral resources.The sections on different types of minerals—energy, construction, metal, and nonmetal—included one on gemstones that was written by George Frederick Kunz, America’s first gemologist.

In 1881, surveyor and Grand Canyon river-runner John Wesley Powell succeeded King as USGS director.Powell concentrated on compiling a national geological map and standardizing geological taxonomy, especially regarding stratigraphic nomenclature and cartographic representation.Powell’s system of geological mapping gained immediate acceptance worldwide.

But politics, economics, and natural events ultimately determined the course of the USGS.During the severe 1886 drought, Congress ordered the Survey to suspend its current work and immediately investigate the West’s aridity, focusing on irrigation, surface and underground water resources, and potential reservoir sites.With hydrology then an infant science and stream-gauging instruments and operators scarce, the USGS trained its own hydrologists and designed and manufactured its own instruments to lay the groundwork for the modern science of hydrology.

By 1890, the West’s prodigious but disproportionate gold and silver production had created a serious imbalance in the supply of coinage and monetary metals.With the nation awash in silver, many politicians now demanded that the USGS forget hydrology and get back to geology—specifically the search for gold.

Amid this latest controversy, Congress cut funding and forced Powell out.Nevertheless, the Survey complied, launching an intensive program of gold exploration with its geologists studying both abandoned and active mining districts, and searching for new deposits.

Geology Garners Greater Appreciation

Until the 1890s, the American mining industry, which profited enormously by crudely exploiting rich mineral veins with “strong backs and sharp drill steels,” had little need for geologists.But as the bonanza veins ran out, the mining industry, along with the rapidly industrializing nation, realized that it did indeed need geologists and other scientists—and quickly.

Fortunately, the USGS was there to provide them.In 1893, Survey chemists devised methods to process the refractory ores at the booming gold camp of Cripple Creek, Colorado.Survey geologists investigated Alaskan gold occurrences in 1895, a year before the great Klondike gold strike.They surveyed the Minnesota iron fields in 1900 and were in Texas in 1903 to help bring in the enormous Spindletop oil field.In 1905, they surveyed the massive, low-grade, porphyry copper deposit at Bingham Canyon, Utah.

Although domestic needs stretched the USGS ranks thin, Congress ordered its geologists and hydrologists to Nicaragua in 1897 to study Atlantic-Pacific canal routes and, following the Spanish-American War, to survey the mineral resources of Cuba and the Philippines.

At all the big mineral strikes, USGS field surveyors, earning only modest government pay, worked side-by-side with miners, prospectors, and speculators who aspired not to advance the Earth sciences, but to become millionaires.Although history books are filled with accounts of those who became millionaires, it was the unheralded USGS field geologists who took the lead in developing the nation’s mineral resources.They did so by methodically identifying and studying low-grade, base-metal deposits that were and are America’s real mineral treasure.

During World War I, shortages of nickel, platinum, tin, potash, and nitrates sent USGS men to the West Indies, South America, and Central America.Employing new concepts of geological inference, the Survey successfully predicted the presence of oil to help bring in major fields in California and the Midwest, and along the Gulf Coast.

Survey Steps In During Wartime

In 1929, the Survey turned 50 years old with 1,000 employees, including 120 geologists.Because the Survey’s investment in basic research had already paid for itself many times over, the old debate about the federal government’s involvement in science was finally put to rest. Chief Geologist Walter Mendenhall, who later became director, justified the Survey’s research programs with words that are still quoted today: “There can be no applied science,” Mendenhall wrote, “unless there is science to apply.”

During World War II, the USGS investigated sites throughout the Western Hemisphere to help alleviate critical wartime shortages of electronic-grade quartz, platinum, optical-grade calcite, beryl, uranium, fluorite, and elbaite.The Survey’s wartime developments included airborne-magnetometry surveys and geochemical-prospecting techniques.

Following the war, USGS maps and mineral surveys were critical to the success of the Colorado-Utah uranium rush that provided the nation with secure sources of uranium for defense and nuclear-power purposes.

The USGS turned 75 years old in 1954 with 7,000 employees and a $48-million annual budget.Although the traditional geologist’s rock pick and survey transit would never be replaced, they were now joined by electron microscopes, mass spectrophotometers, advanced chemical-analysis methods, computerized statistical analyses, and airborne radiometric, gravimetric, magnetic, and photogrammetric surveys.

In 1959, with American and Soviet Earth satellites in orbit, the USGS was ordered to study impact craters preparatory to photogeologic lunar mapping.The Survey also began training National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) astronauts at its new Astrogeological Laboratory in northern Arizona.

USGS Sparks 1960s Gold-Mining Boom

In its greatest success of the 1960s, the Survey geologically inferred the

existence of massive deposits of low-grade, disseminated gold ores in northern Nevada.Although this work received little public attention, it triggered what became America’s greatest gold-mining boom ever.Nevada’s mines have since yielded more than 200 million troy ounces (4,680 metric tons) of gold.

In 1971, the USGS, now with 7,200 employees and backed by an annual $200-million budget, published The National Atlas of the United States of America, a compilation of 700 physical, historical, economic, sociocultural, and administrative maps.Needing a decade to complete, it remains the most comprehensive atlas ever published.

In 1970, the USGS conducted the environmental and geological surveys for the Alaska Pipeline and even entered the field of marine geology.Working closely with NASA, it also began studying lunar and Martian geology, and helped to design and operate the Earth Resources Technology Satellite (ERTS-1), which used photographic and remote-sensing methods to investigate the Earth’s geology, hydrology, cartography, and geography.And in 1972, USGS geologist-turned-astronaut Harrison Schmidt collected rock samples on the moon.

The Survey also completed one of its largest projects ever—the topographical mapping of all 3,679,245 square miles of the United States.While post-World War II aerial-photogrammetry techniques greatly accelerated the mapping process, it also required a massive revision of much previous mapping that was based on ground surveying.

USGS cartographers had emplaced countless thousands of circular, engraved bronze benchmarks as surveyed triangulation reference points.This duty was later passed on to the United States Coast & Geodetic Survey (now the National Geodetic Survey).These benchmarks, many engraved with the name of the USGS, are still used today.

Centennial Recognition

In 1979, the USGS was recognized as one of the few governmental agencies to survive for 100 years with its original name and mission basically unchanged, although substantially expanded.

During the next few years, the massive eruption of Washington’s Mount St. Helens volcano and a series of unusually intense California earthquakes gave the Survey another responsibility—identifying and investigating geologic hazards.Today, the Survey operates several volcano observatories and a global seismic network and provides the public with earthquake- and volcano-notification services.

One of the USGS’s most popular public-interest publications, a pamphlet titled “Prospecting for Gold in the United States,” was released in 1991.Although brief, it laid out the basics of gold prospecting in readily understandable language.It was distributed in rock shops throughout the country. Reprinted many times, it is still available today and can be found on-line.

The USGS took on new responsibilities in 1996 when Congress abolished the United States Bureau of Mines.Founded in 1910, the Bureau of Mines had conducted research into and published information about, mining, mineral processing, and mineral resources.

For decades, field mineral collectors and prospectors benefited from its detailed reports on mining districts (some of which duplicated USGS work).When the Bureau was abolished, the USGS carried on its mineral-information duties and continues today to compile and publish mineral-industry surveys, mineral-commodity summaries, and minerals yearbooks.

Changing Times and Techniques

In 2008, keeping pace with advancing technology, the USGS abandoned all traditional methods of surveying, compiling, and updating topographical maps, relying instead on cartographic data from the National GIS Database.The GIS (Geographic Information Systems) is a computer-based tool that analyzes, stores, manipulates, and displays geographic information in map form.

Among the Survey’s many research centers is its Core Research Center in Denver, Colorado.Established in 1974, this facility stores, catalogs, and makes available to researchers thousands of miles of drill-core sections and cuttings that represent much of the subsurface geology of the United States.

Also in Denver, the USGS operates the National Science Foundation’s National Ice Core Laboratory, which preserves, curates, and studies ice cores from ice-capped and glaciated regions worldwide.Its freezer-storage facility contains 25 miles of ice cores, which are records of past and present climatological change, historic and prehistoric volcanic eruptions, and volcanic and man-made pollution sources.

The USGS Library at the USGS Headquarters in Reston, Virginia, is the world’s largest Earth science library with more than three million items ranging from historic field notebooks and rare books to current reports and photographs.Among them are more than 150,000 publications authored by Survey scientists for both publication in scientific journals and distribution to the general public.

The USGS Library also shelves gemologist George F. Kunz’s collection of thousands of rare books, pamphlets, articles, and personal notes on gems and gemstones.Following Kunz’s death in 1932, his estate sold his entire personal library to the USGS for the sum of one dollar.

Modern-Day Survey Status

Today, the Survey, with 10,000 scientists, technicians, and support staff, backed by a $900 million annual operating budget, is headed by noted geoscientist and former astronaut Dr. Jim Reilly.The Survey’s motto is “Science for a Changing World.”It continues in the broadest sense to study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, and its natural hazards in six mission areas: climate and land-use change; core science systems (biology, geology, geography, and hydrology); ecosystems; energy; minerals and environmental health; natural hazards; and water.

Since the USGS was founded, its scientists have discovered and described many new minerals, or had new minerals named for them, a tradition that continues today.Among the newest mineral species recognized by the International Mineralogical Association is finchite, a hydrous strontium uranyl vanadate. Survey geologist Bradley Van Gosen collected the type specimens in west Texas in 2015 and helped describe them.In 2017, the new mineral was named finchite, in honor of the late Warren Finch, a world-renown, USGS uranium geologist.

The USGS has provided the nation with enormous scientific and

economic benefits. And rockhounds, mineral collectors, and prospectors are among those who have benefited greatly. Remember, too, that most of the commercial, field-mineral-collecting guidebooks ever written are based heavily on USGS maps and field-survey reports.

To see what the USGS has to offer, check out www.usgs.gov.This big, easily navigated, educational site is loaded with historical and up-to-the-minute information on all aspects of the Earth sciences. Field mineral collectors and prospectors will agree that, at least in the case of the United States Geological Survey, their tax dollars have been well spent.

Author: Steve Voynick

A science writer, mineral collector, and former hard rock miner, he is also the author of many references including, “Colorado Rock Hounding” and “New Mexico Rockhounding.”