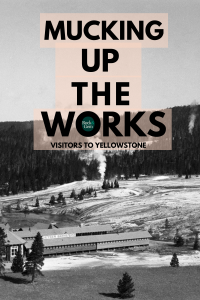

Visiting Yellowstone was popular long before it became the first national park in the world over 150 years ago. Its abundant wildlife and surreal landscape include over 10,000 thermal features. People flocked to witness these other-worldly spectacles. Yet, human influence undoubtedly changes things, and there are some resources and experiences that have never been the same.

Evidence of people visiting Yellowstone and behaving badly appears almost daily on social media channels, but I was somewhat shocked at the long history of guests’ behavior until I researched hundreds of photos from the 1890s to around 1940 for the book, Found Photos of Yellowstone: Yellowstone’s History in Tourist and Employee Photos. My longtime friend and Yellowstone aficionado, Mike Francis, collected these images from family photo albums and private collections from over 50 years. What people did a century ago surprised me but made me feel slightly better because it’s not just modern-day visitors who make faux pas.

Visiting Yellowstone & Stepping Through Mammoth Hot Springs

The Northern Pacific Railway marketed vacationing in Yellowstone National Park to wealthy Eastern travelers as the “it” place for them to be. The railroad promised tales of visiting Yellowstone for an adventure but at a cost to the landscape.

Mammoth Hot Springs was the first stop for guests who traveled via railroad to Gardiner, then piled on one of the stagecoaches to the National Hotel (later the Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel).

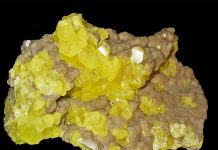

The bubbling and spurting thermal features enthralled visitors and they naturally wanted to leave their mark or take a piece home with them. In the 1880s, people often scratched their names into the thermal features. Visitors even hacked off pieces to take home with them.

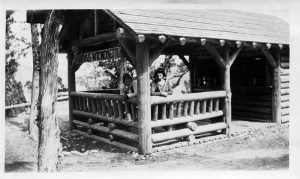

At the Mammoth Terraces, there were no boardwalks as there are today, so people visiting Yellowstone walked all over the fragile travertine formations to gain a better perspective. Women in ankle-length skirts climbed right along with the men, who looked like they were heading to a luncheon, rather than exploring a wild area.

A popular tourist souvenir involved creating travertine-encrusted items to take home. Purveyors set up ladders along the terraces where they attached small items, to allow the mineral-rich waters to run over them. In three days, they were coated with a brilliant white, almost marble-like appearance from the calcium carbonate from the water.

The “Specimen House,” opened by Ole Anderson in 1897, sold these curiosities, along with sand art scenes made of different colored sand collected from the park in glass jars.

The Army to the Rescue

Even before four million visitors descended upon the park as it is today, Yellowstone was being loved to death. It was a free-for-all by early entrepreneurs who ran tourist facilities, including camps where they laundered materials in hot springs. Vandalism by the guests was rampant. Poachers also viewed Yellowstone as a productive opportunity and continually pressured wildlife. There was no National Park Service during this era, but fortunately, Congress sent the U.S. Army to save the day.

In 1886, Company M, First United States Calvary, built a handful of buildings at the base of the Mammoth Terraces as the temporary Fort Sheridan. The first buildings of Fort Yellowstone, which we see to this day, were finished in 1891. The military presence remained in the park until 1917, with 324 soldiers holding post in 1910. These men guarded natural features, pursued poachers and assisted the public until Congress created the National Park Service in 1916 and park rangers stepped into this position.

Courtesy Michael H. Francis Historical Collection

Visiting Yellowstone: Guests Affecting Thermal Features

Old Faithful Geyser is arguably one of the most recognized symbols of the park. Today, it makes the news when people walk along the fragile mineral-laden terrain leading to the geyser, but it was nothing out of the ordinary when visiting Yellowstone a century ago. The difference is we now understand how even minor damage remains on these features. An interactive feature that delighted guests for decades was Handkerchief Pool, located at the southern edge of Rainbow Pool in the Upper Geyser Basin. In the early 1900s, the National Park Service installed a paved walkway, and there was a concrete ring around the edge of Handkerchief Pool. Visitors, including President Calvin Coolidge’s family, loved the magical action of this thermal feature. They would drop a handkerchief, or some other piece of cloth, in the pool, where it was sucked into the depths for several minutes before being spewed back to the top of the water clean as if it went through the wash cycle. Unfortunately, the fun ended as people continually tossed coins and trash, and ultimately a log, into the feature, which plugged up the thermal plumbing.

West Thumb Geyser Basin

At West Thumb Geyser Basin near Yellowstone Lake, the renowned Fishing Cone was popular since the 1872 Hayden Expedition. It became a convenient hot spring because anglers could catch a fish, dip it in the thermal feature and cook it on the line. In 1920, the park created a regulation stating that visitors were no longer allowed to cook live fish, and shortly after, the Fishing Cone became completely off-limits for dinner preparation.

Norris Geyser Basin

In the Norris Geyser Basin, during the early days of visiting Yellowstone, tours stopped along the road in proximity to Minute Geyser, which erupted up to 40 or 50 feet every 60 seconds. As people often did, and still do, they tossed coins into the clear, bubbling waters as they waited. Over the years this clogged the vents causing the Minute Geyser to stray off its regular schedule with irregular eruptions that spurt just over a foot high. Ear Spring Geyser gave us a glimpse of the items often responsible for clogging up the works in 2018 when the normally quiet geyser erupted 30 feet in the air, spewing a myriad of debris. Located on Geyser Hill in the Upper Geyser Basin, there hadn’t been a strong eruption since 1957, two years before the monumental Hebgen Lake Earthquake.

When it erupted in 2018, it shot up over 100 coins, a cement block, a drinking straw and a pacifier from 1930.

Courtesy Michael H. Francis Historical Collection

Don’t Feed or Pet the Wildlife!

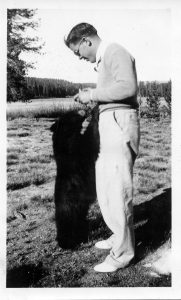

From the beginning, bears, especially black bears, figured out that proximity to people meant easy calories. There were frequently black bears loitering outside the kitchen entrance to any of the hotels or camps. Many wandered through the cabin or tent areas looking for a handout.

Cars made their debut in the park in 1916, and within a few years, bears figured out that traffic equaled a mobile buffet. There was a famous black bear that was dubbed Jesse James, who was known to “hold up” tourists in their vehicles until he was given a treat. By the 1920s, there was some degree of discouraging tourists from feeding the bears, although even officials considered that part of the experience of visiting Yellowstone.

Bear Lunch Counters

There were specific bear lunch counters, as they were called, set up at Old Faithful and Canyon, where restaurant waste was spread out for the grizzly bears to eat during the evening show. Rangers would sometimes sit astride a horse with the bears feeding behind them, as they talked to the visitors lining the bleachers.

In other parts of the park, people visiting Yellowstone could pay a little extra to the hotel staff to accompany them out on the garbage wagon. Black bears would typically meet the nightly run and it was an excellent opportunity for a photo and a close-up experience. After World War II, the Park Service was able to clamp down on this behavior.

Bison Population

When Yellowstone was established, the once-abundant bison were nearly extirpated. The herds were restored and bison now roam the roads and have the right-away pretty much anywhere they travel. For locals, summer begins with the first “tourist toss” of the season as guests step too close to these one-ton creatures that can run 35 mph and move faster than one can imagine.

Courtesy Michael H. Francis Historical Collection

Visiting Yellowstone: Attractions That Are No More

From 1914 to 1951, people visiting Yellowstone could enjoy the multiple indoor pools of the Geyser Water Swimming Pool. Located in front of Old Faithful Inn, across the river from Beehive Geyser, water from Solitary Geyser was piped in for the pools. The structure went through several renditions, eventually growing into a structure where the main pool could hold well over 100 people and there was a 25-feet high lifeguard tower.

As early as 1884, visitors to Devil’s Kitchen, the crater of an extinct hot spring, could use a ladder to explore the 35-foot-deep and 75-foot-long area. It was described as warm, dark and humid. In the early days of its discovery, the bottom was littered with the bones of animals. Guests reported feeling a “queer sensation” and a “desire to seek fresh air.” Undoubtedly, because of the noxious gases found in some of Yellowstone’s caves.

In 1925, the “Devil’s Kitchenette” sold ice cream and cold drinks to visitors. The Park Service finally closed the feature in 1939.

Noting what visitors have done in the past is a good reminder of why we need to care for Yellowstone, and all of our natural resources, as a way of ensuring our grandchildren and future generations can appreciate their beauty and wonder unscathed.

This article about visiting Yellowstone National Park previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Amy Grisak.