What does a petrologist do? Technically, petrology is the branch of geology that deals with the origin, composition, structure, and alteration of rocks. Here’s how Alisha Clark became a petrologist.

Alisha Clark has been fascinated with rocks, their development in the earth and the interplay between them and humankind since she was a child. She’s the assistant professor of geological sciences at the University of Colorado, Boulder and holds a Ph.D. in geology. She says becoming a scientist is the best way she knew to stave off boredom in her professional life, channel her creativity and use problem-solving skills daily.

ROCK & GEM:

What exactly is petrology? How is it different from geology?

ALISHA CLARK:

When you tell somebody you’re a petrologist, you get asked a lot of questions about oil. Petrologists study rocks. Rocks are effectively the main geological record that we have. Petrology has three subdivisions: igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary. I like igneous.

R&G:

Why is igneous your area of interest?

AC:

The igneous processes are related to those where there is magma around and silicate melts are the main player in the processes for the Earth. I tease some of my colleagues that rocks are just the old fossilized dead parts, but the active, vibrant part is the melt. I think in part that is why I really like igneous processes. It’s trying to understand both how melts work inside the Earth, and then also looking at their signatures either in rocks or through geophysics to see what’s going on where they are and how they function.

R&G:

What has your experience been interacting with mineral collectors?

AC:

A lot of times petrologists are interested in what can be considered the boring rocks as far as mineral collectors are concerned.

We can often get schooled on mineral identification for really rare things by your average mineral collector because they have that amazing breadth of knowledge. It always impresses me when I get a mineral collector student in my class.

R&G:

Can you relay your journey in becoming a scientist?

AC:

I hold an undergraduate plus a master’s and Ph.D. in geology from the University of California, Davis. I always loved rocks —a gravel driveway was my favorite thing as a two-year-old. We had a house with a deck and a concrete pad and my older brother would help me throw rocks off it and break them open to look at the insides.

I initially went to college for chemical engineering, which is kind of funny because it’s sort of the industrial counterpart to what I do now. I ended up taking a bunch of graduate classes in that department but it was too regimented for me. Then I became a medieval studies major, but I missed the science problem-solving side of things.

If I didn’t figure out what I wanted to do in two years, I was going to go be a park ranger. It was at the end of those two years that I took a geology course. With geology, you’re trying to piece together a puzzle where you’re missing most of the puzzle pieces. It can always be frustrating to some of the students who would like to have a set answer. You get students who like the flexibility and those who are frustrated that there are a bunch of reasonable interpretations to every problem.

R&G:

What led you to pursue a Ph.D.?

AC:

I finished my undergrad degree and then worked in a professor’s lab. I loved working in the lab. I got to build and design experiments for people in the university.

There’s a crossover to material science. I did work related to new technologies. I got to play in the lab every day. My advisor told me I should get a master’s. During graduate school, I ran experiments at Argonne National Laboratory Advanced Photon Source. It’s a particle accelerator used for research. I tried to measure the density of silicate melts at high pressure, which is a tricky thing to do. Then, I thought maybe I’d like to become a staff scientist there. To do that, I needed a PhD.

It’s so rare for any of us in my field (petrology) to come into college wanting to do it. Most of us don’t know it exists. It takes a while to find it.

R&G:

Can you take us deeper into your role in the classroom?

AC:

The University of Colorado, Boulder is classified as an R1 — doctoral university. We grant Ph.D.s. I have Ph.D. students but I also teach undergrad as well. I started teaching there in the fall of 2019 and then the pandemic hit. I’m excelling at being a first-year professor in my third year (laughs).

Some of the classes I teach include mineralogy, our deadly planet (hazards), mineral physics and petrology. It’s been nice to be back on campus this year. Teaching remotely was tough on everyone and it’s hard to look at rocks in class when we aren’t physically together – pictures just aren’t the same.

R&G:

Can you describe a day in the life of a petrologist?

AC:

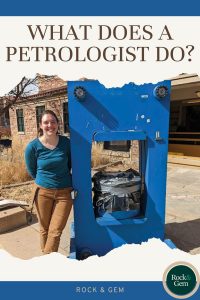

I’m an experimental petrologist — which is the most fun. All these rocks end up exposed on the surface of the Earth and what we do in an experimental world is we say we think this rock is telling us about something that’s happening in the interior or back in time or under these processes, etc. How we test that is we have these big machines, sometimes tiny machines, that can simulate the pressures and temperatures inside the earth.

Some petrologists go out and they look at rocks and they make maps of fields or things like that, or there’s more of a sort of geochemical petrologist who goes out and collects rocks and uses crystals inside of those rocks to get dates of when different eruptions happened or when a particular rock formed.

R&G:

Can you tell our readers about a project you are working on?

AC:

One of the projects that I am working on is the very opposite side of the coin to what you would think of as a seismologist or geophysicist. If there’s an earthquake, a seismologist or geophysicist would go out and say it took this much time for the energy wave generated by the earthquake to end up on this side of the other side of the earth.

A seismologist can take a bunch of these wave speeds and then map out little blue and red blobs: where there are red blobs the seismic wave speeds are traveling slower than they would in the “average” Earth, other scientists say it’s likely hot and perhaps molten like a mantle plume. Where there are blue blobs the seismic wave speeds are traveling faster than they would in the “average” Earth, and so scientists say it’s cold and dense, perhaps like subducting oceanic slabs.

What I do is I say, well, actually, what the seismologist did was tell us that the seismic waves were traveling at 8 or 8.5 kilometers per second. How fast do seismic waves actually travel through rocks inside the earth? And I go into the lab and I make those measurements by hooking up lots of small little electrical diagnostics to machines that can squeeze rocks to pressures and temperatures deep inside the earth.

R&G:

Then what you do is conduct simulations?

AC:

Yes, it’s a simulation in certain aspects, but we are careful when we say that because there are people that do computer simulations and those are different. The rocks are really at the pressures and temperatures that exist inside the Earth when we squish them in our machines.

R&G:

How do you divide your time as an experimental petrologist?

AC:

If you’re a petrologist in academia, your job is usually split into three parts; teaching, research and service. Service is participating in professional societies such as the American Geophysical Union. As a scientist, whether you’re working for a company or in a lab, you’re trying to publish your work in peer-reviewed journals and you also read other people’s work for them.

R&G:

Is there much travel involved with this line of work?

AC:

Yes, I travel a lot for experiments. I don’t travel so much for fieldwork, although I have friends in petrology who do. I always say that my field areas are Chicago and New Mexico and therefore I have the best food out of everyone!

R&G:

Did you travel much as a university student?

AC:

I traveled a lot as a student to run experiments, every three months or so, mainly to Chicago. I finished my Ph.D. while living in Denmark. My first postdoctoral position was in Paris. I worked at a big particle accelerator there. For the particular branch of petrology that I’m in, there’s a lot of cross-pollination with England, France, Germany, Japan and Australia and you get to go on research trips where you can travel to these countries.

R&G:

Can you describe other aspects of being a petrologist?

AC:

My closest industry is material science.

It’s working for companies like Corning, which specializes in glass and ceramics.

They hire a lot of geologists, which is weird to some people, but if you think about it, ceramic is a rock, and any glass is basically just frozen magma.

A lot of times people with jobs in the industry do research that is in part focused on the goals of the particular industry that they’re working in. They’re doing more report writing and I don’t write so many reports —I write papers.

R&G:

What advice would you give someone interested in pursuing a career in petrology?

AC:

I just think it’s great for people at any age looking for a career change to consider geology because it’s all of the sciences related to the Earth. We don’t necessarily have some of the prestige of being a physicist, but we go on more field trips. If you like science and you like gray areas, it’s a great place to be.

R&G:

What makes petrology a relevant field in the 21st century?

AC:

Quite a few things. If you think about it, besides plant-based materials, everything around us basically comes from a rock. Understanding those materials is important. Whether you’re talking about understanding how things form so you know where to look for aluminum to make building materials, or whether you’re talking about understanding the processes that change the properties of glass or effectively, magma, that’s what goes into our window glass or fiber optic cables. It’s nice to work at that sort of nexus between things that can apply directly to people and sort of fun, big science questions trying to understand how the earth formed.

This story about how to become a petrologist previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Sara Jordan-Heintz.