What is Zircon? After radiometrically dating tiny zircon crystals from Western Australia to more than 4.4 billion years, geophysicists now recognize zircon (not to be confused with zirconium and cubic zirconia) as the oldest material on Earth. Data obtained from the study of these crystals has dramatically revised the understanding of our planet’s beginnings and pushed back the appearance of life on Earth by several hundred million years.

“A diamond is forever,” the classic advertising slogan of the De Beers Diamond Syndicate, refers to both the durability of diamonds and to the love relationships they represent. While scientists don’t profess to be experts on matters of the heart, they do know about gemstone durability, especially the Mohs Scale of Hardness. And considering recent scientific revelations, the diamond slogan could be rewritten as “a zircon is forever.”

Zircon the Gemstone

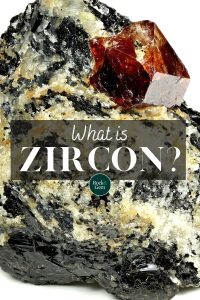

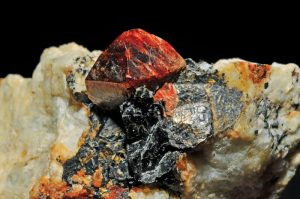

Zircon (zirconium silicate, ZrSiO2) consists of silicon, oxygen and zirconium. With its wide range of colors and substantial hardness (Mohs 7.5), zircon has served as a gemstone since antiquity. Some biblical scholars suggest that zircon was among the 12 gemstones in the sacred breastplate of the high priest of the Israelites that dates to 1450 B.C. In later medieval times, zircon was thought to promote sleep and bring prosperity, honor and wisdom to its wearers.

Wikimedia Commons

The most common of zircon’s many colors is brownish-red. Yet it was blue zircon that enjoyed great popularity in Victorian-era jewelry. By 1900, colorless zircon had become the preferred diamond simulant, thanks to its high index of refraction (1.92-1.96) that gives properly cut zircon gems a fiery, diamond-like glitter. To add to zircon’s gemological credentials, several large, reddish stones are included in the British Crown Jewels collection. Zircon is the birthstone for December.

Nevertheless, as a gemstone zircon does have an image problem. Unlike ruby and emerald, it lacks a dominant identifying color. And because of its previous role as a diamond simulant, zircon is still associated with imitation. Furthermore, zircon is often confused with the modern diamond simulant cubic zirconia (CZ), which is not zircon at all, but a stabilized, synthetic zirconium oxide.

Wikimedia Commons

Zircon and Uranium

Because of a mutual chemical affinity, zircon usually contains traces of the radioactive element uranium. The uranium atom’s unstable nucleus undergoes continuous atomic decay, emitting ionizing energy as particles and rays while disintegrating into a series of unstable isotopes that eventually ends with the stable form of lead.

Uranium’s radioactivity causes some zircon crystals to undergo metamictization, which occurs when radiation displaces electrons within the zircon lattice to slowly degrade the crystal structure. The effects of metamictization include rounded crystal edges; curving faces; separating cleavage planes; color alteration; and decreased hardness, density and transparency.

Metamictization can sometimes degrade transparent zircon crystals into opaque, amorphous masses. However, metamictization is not a problem with zircon gems. Radiation levels are far too low to be hazardous and the physical effects of metamictization in zircon become apparent only after millions of years.

The “Clock in the Rock”

The marriage of zircon and uranium makes possible very long-term radiometric dating. Rates of atomic decay are expressed in terms of “half-life,” the time in which radioactive isotopes lose 50 percent of their radioactivity. The uranium-238 isotope has the longest half-life at 4.5 billion years.

When igneous rocks solidify from magma, uranium is often present in their compositional minerals. Because atomic disintegration progresses at known, precise rates, measuring the ratios of the decay-chain isotopes reveals the extent of atomic decay and thus the time that the mineral crystallized.

To date extremely old materials, uranium must be trapped within an extraordinarily durable, abundant and widely distributed crystal such as zircon. Zircon is inert and insoluble, while its crystal structure assures survivability even in the high pressures associated with geological upheaval and burial. It’s very high melting temperature enables zircon to endure even the extreme temperatures of high-grade metamorphism.

Zircon can survive billions of years of physical and chemical weathering, transport, and redeposition, while its traces of uranium steadily tick away as the clock in the rock.

Wikimedia Commons

The Hadean Time Capsule

Geophysicists have radiometrically dated tiny zircon crystals from Western Australia’s Jack Hills to 4.404 billion years. These crystals formed during the Hadean Eon (4.6-4.0 billion years ago), the earliest and least understood of the Earth’s geological time divisions. The Hadean Eon was named decades ago when scientists believed that volcanoes and lava fields dominated the primordial Earth and created “hell-like” conditions unsuitable for life.

But data obtained from the Jack Hills zircon crystals paints a radically different picture of the Hadean landscape, one where the Earth’s crust formed much earlier than previously thought. Furthermore, the ratios of oxygen isotopes trapped within these zircon crystals indicate that an atmosphere and oceans already existed and that life was therefore already possible.

The Jack Hills zircon crystals were originally part of a granitic rock that completely weathered away. These crystals then mixed with sediments that lithified much later and metamorphosed into the 3.3-billion-year-old quartzite-conglomerate formation that geologists call the Jack Hills Quartzite. Polished slabs of this orange-brown meta conglomerate with their tiny reddish zircon crystals are now sold at gem and mineral shows and online.

So while diamonds might be “forever” in matters of love, when it comes to the radiometric dating of the early Earth’s oldest known crustal fragments, it seems that what is forever are zircons.

This story about what is zircon previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Steve Voynick.