From clay to glaze, it’s important to know which minerals are used in pottery as they are ever-present in the business and art of pottery. This is nothing new as people have been forming objects from clay and then heating them for durability and permanence for more than 20,000 years.

Pottery Clay Minerals

Clay forms the basis for pottery and is made up of many different minerals. Because they can form large deposits, the most common clay minerals used by potters are kaolinite, montmorillonite and bentonite. These minerals are composed of hydrous aluminum silicate. They have a layered sheet-like structure, small particle size and usually contain impurities such as iron. They are all soft and plastic when wet. This allows potters to mold or model moist clay into a form that will be retained upon drying.

As clay dries, it becomes hard, brittle and non–plastic. When heated to the point of vitrification, the clay particles melt and fuse making the form permanent. The actual temperature to vitrify the clay depends on the type of clay and its ratio to other ingredients in the clay body.

Today commercial clays are mixed from materials mined at different locations around the world and are ground into fine powder form. They are packaged and sold regionally to be used for specific firing temperature ranges. (Author’s Note: Much of the Ball Clay I use comes from Old Mine #4 in Mayfield, Kentucky. I get alkali feldspars from the Black Hills of South Dakota and plagioclase feldspars from North Carolina.)

Potters divide ceramic clay bodies into groups with general firing ranges: earthenware (1750-2000?F), stoneware (2010- 2370?F) and porcelain (2200-2500?F). Potters who choose to mine their clay or glaze ingredients must do a lot of trial-and-error testing to adjust a suitable clay body or glaze that fits their firing conditions.

Most Common Clay Minerals

Clays form through chemical weathering when carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and soil is dissolved into rain or groundwater creating an acidic solution that permeates feldspar-rich rocks like granite.

The alteration from feldspar to clay occurs gradually over long periods. Feldspars, such as orthoclase, can alter directly into the clay mineral kaolinite and remain in the original place of formation or be transported via erosion and deposited in sedimentary layers in lakes or marine basins. Clay deposits comprise common widespread sedimentary rocks around the globe and are even known to occur on Mars.

Major groups of clay minerals include the kaolin and smectite groups. The kaolin group contains the minerals kaolinite, dickite and halloysite. The smectite group contains the minerals montmorillonite, nontronite and beidellite.

How a Potter Shapes Clay

There are many methods to form, shape or mold clay. A ceramic artist may dedicate decades to learning and perfecting a broad range of techniques. Because wet clay particles move and slide against one another, clay may be expanded, stretched and bent while additional pieces may be joined or cut away. This plasticity of clay is the significant characteristic that makes working with clay unique. It is unlike working with stone or wood where a grinder or blade can only remove matter from a fixed piece of material.

An experienced craftsperson or artist can expand a ball of clay into a cylindric form and then stretch or constrict it further into a precise shape while spinning it on a potter’s wheel. After the newly shaped pot has dried, it is fired in a kiln just hot enough to evaporate the physical water and prepare it for the glazing process. At this stage, known as bisque, the pottery remains porous and will allow the applied glazes to absorb into and adhere to the pot.

Ceramic Glazes

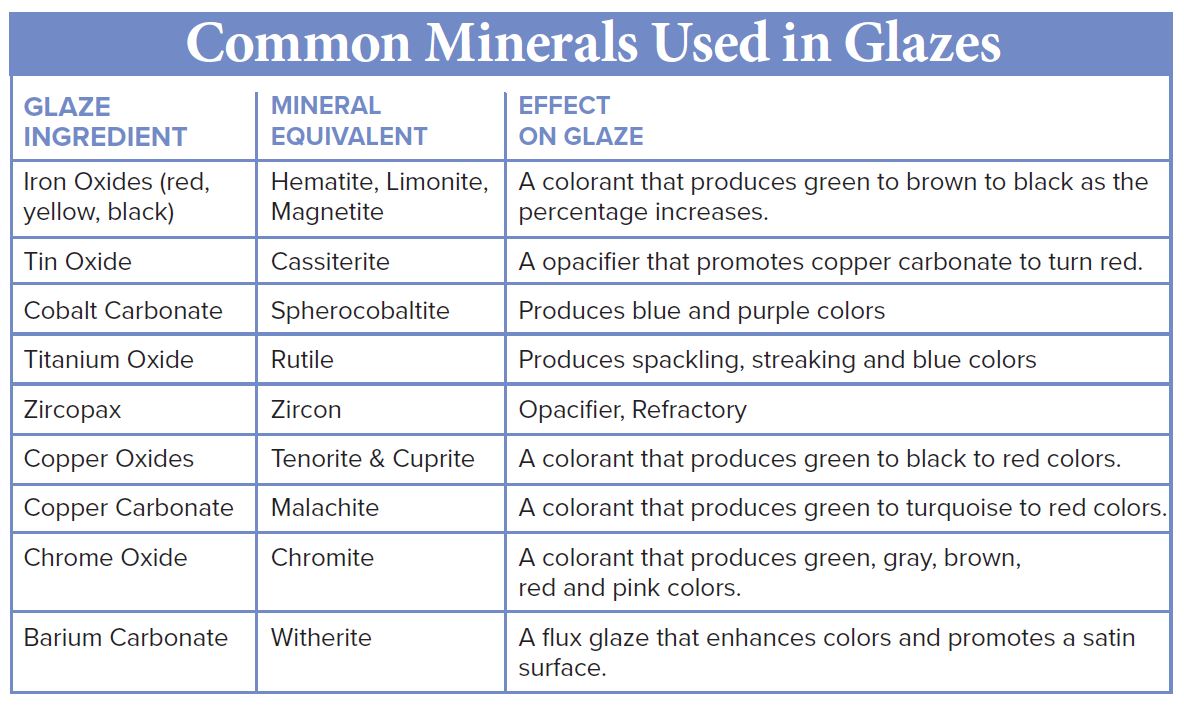

Glazes are thin coatings of finely ground minerals that are applied to the surface of pottery by brushing, dipping, pouring or spraying. When fired in a kiln, they melt and fuse to a pot giving the pot it’s color and finish, either gloss or matte. Some glazes are further used to line functional pottery to make them sanitary and easy to clean. In the case of some low-temperature clays, there is a glaze to make them watertight. Glazes also provide artistic decoration.

Glassy-looking glazes are primarily silica (quartz) but because quartz melts at such a high temperature (3139?F), fluxes are added to lower its melting point. Minerals and rocks rich in sodium, lithium, and potassium (alkali metals) such as feldspars, nepheline syenite, and spodumene do a great job causing glazes to melt at lower temperatures.

After adding a flux, stabilizers (also called refractories) are added to the glaze so that it doesn’t just flow down and off the pot during heating. Stabilizers are rich in aluminum-containing minerals and clays such as kaolinite, ball clay and grolleg (pre-fired clay ground into small granules). Bentonite, impure absorbent clay consisting primarily of montmorillonite is often added in small percentages to glazes to keep the small glaze particles from settling when in a solution of water.

Fired Ceramics

After applying glaze to a bisque (fired for the first time) pot, the pottery is heated in a kiln. Kilns may be fueled by burning combustible materials such as wood, oil and natural gas or they may have electric heating elements. Different methods of heating can affect atmospheric conditions inside the kiln and influence glaze colors. Regardless of atmospheric conditions, firing to the point of vitrification makes the pottery watertight and permanent. Properly vitrified pottery will last for thousands of years – or until you drop them!

This story about what is proustite appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story and photos by Troy Schmidt.