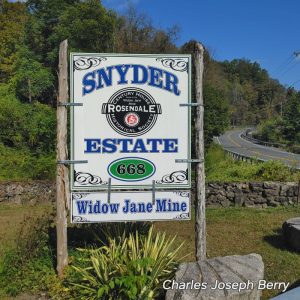

The Widow Jane Mine has an intriguing name and an intriguing history. Yes, there was a Jane who was a widow and yes, there was a mine. But there’s oh so much more to the story behind the 275-acre Snyder Estate and Widow Jane Mine on Route 213 in Rosendale, New York.

A story that begins like a Sphinx’s riddle: How did Jane predecease her husband if she was but once a widow?

The Snyder Homestead

It depends, according to The Century House Historical Society (CHHS) at the Snyder Estate, because while there was only one mine there were two Janes.

Let’s start at the Snyder homestead, where, for more than two decades before the American Revolution, the family had put roots farming land down along Rondout Creek.

Christopher and Deborah Snyder commissioned a house and a gristmill along their creek in 1809 to their newly wedded son, Jacob Louw Snyder. Sixteen years later, Jacob ceded a portion of that property to John B. Jervis, allowing Jervis’s Delaware & Hudson Canal Company to keep digging its new canal along its intended route.

But with a caveat: The D&H had to not only build Snyder a boat slip where he too could ship his produce to market on the new waterway, they had to build a bridge to reach his flour mill, too. Jervis said yes and the decision was amply rewarded.

Canal construction had hardly begun when it struck proverbial pay dirt: Massive deposits of dolostone with just the right amount of clay minerals that once pulverized and mixed became natural cement comparable in quality to what was being used at the time to build the Erie Canal.

Rock & RoadPlan a rock and road trip to this acoustically and geologically inspiring spot. Learn more at CenturyHouse.org. “Please leave a donation at the parking lot kiosk when you visit! The 2025 museum season starts in May,” summarizes CHHS board president and Rosendale Library archivist, Henry Lowengard. Things close in October with a popular annual performance of Dracula. Find more information at WidowJaneMine.com. If such cement could build one canal it should be able to build another, and it did. Snyder leased the southeast corner of his Rosendale property to Watson Lawrence, who opened the Lawrence Cement Company. Snyder kept reinvesting profits into upgrading his equipment and its technical quality before setting his sights on contracts for some of the largest-scale, most high-profile government construction projects of the day, like New York City’s Croton Aqueduct. |

Courtesy L.A. & Charles Berry

Who Was Jane?

Jacob, our industrious newlywed, and his wife, Elizabeth Catherine (nee Hasbrouck) Snyder, had two children: James (1819) and Catherine (1831). On May 4, 1838, James took as his bride, Jane LeFevre.

James would not live to see his 33rd birthday. Jane would spend 52 years a widow and see the arrival of the 20th century before passing, at age 83, in Rosendale on April 15, 1904.

Snyder Estate archives identify her as the “Jane” of the Widow Jane Mine. But she was not the only Jane in this cemented family.

“Jane [LaFevre] was probably sister-in-law of Catherine, wife of Andrew Jacob Snyder I (1799-1874), who ran the Snyder & Sons Cement Company on the estate,” notes the Century House and Rosendale Historical Society. “Jane owned property with daughter Maria Snyder Sheeley, adjacent to Cottekill Road, in 1903 and probably before that.”

Interestingly the historical society story says, “There was no mining on Jane’s property.”

The Other Jane

The other Jane is Jane Munn, wife of John James Snyder, son of Catherine and A.J. Snyder I. This Jane was never a widow, instead predeceasing her husband John James, who later remarried a widow named Rebecca Wager, not Jane.

So who was the Jane – or widow – of this mine? A little bit of a secret taken if not necessarily to the grave then at least to the quarry.

How Rosendale Built History

What became known for almost a century and a half as Rosendale Natural Cement was used in the construction of some of the greatest landmarks and structures in America, including not only Jacob’s coveted Croton Aqueduct but also the Brooklyn Bridge, Grand Central Terminal, Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels, wings of the U.S. Capital, the first 150 supporting feet of the Washington Monument, and the foundation for the Statue of Liberty.

“Rosendale Natural Cement is known for endurance and has achieved the highest respect in the industry,” cites the free literature provided by the Rosendale Historical Society at the trailhead en route to the Widow Jane Mine. “In 1836, workmen [with the Delaware & Hudson Canal] noticed stone on the Snyder farm that changed appearance when heated while making their coffee. They brought this rock to a blacksmith shop in High Falls. As they experimented with the rock, an engineer in charge of construction for the canal said that he believed it to be natural cement rock. He was correct.”

By 1870, the RHS says the number of cement companies supplying Rosendale Natural Cement to the nation grew to fifteen; each manufacturer had their own recipe.

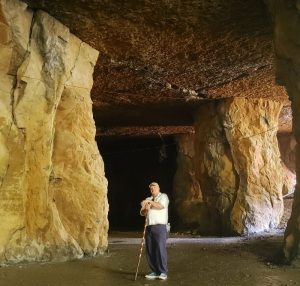

Extracting Cement at the Widow Jane Mine

An Overview of the History and Economic Geology of the Natural Cement Industry at Rosendale, Ulster County, by Dietrich Werner and Kurtis C. Burmeister said, “The Rosendale region of southeastern New York State is widely recognized as the source of the highest quality natural cement in North America. Rosendale Natural Cement’s reputation stems from the unique composition of the clay-rich layers of dolostone in the Upper Silurian Rondout Formation from which it is manufactured. Miners utilized room-and-pillar techniques to extract this dolostone from strongly deformed strata, creating unique bedrock exposures in mines that are something of an engineering marvel. The exposures resulting from these mining activities have long attracted the attention of geologists for research and education.”

Courtesy L.A. & Charles Berry

Quarry Leggos

The massive underground supporting pillars were called “leggos” by its quarrymen because, should one be removed, it would cause the earth above to “let go.”

“Production of natural cement transformed extracted dolostone into barrels of cement through a labor-intensive process involving calcination in kilns, cracking, and grinding,” the abstract continued. “Barrels of cement produced were quickly shipped at competitive prices via the Delaware and Hudson Canal, which directly connected the Rosendale natural cement region to major shipping avenues.”

By the start of the 20th century, Portland (Maine) cement entered the scrum, undercutting its competitors, and Rosendale’s cement industry dried up. But with a new century’s renewed interest in repairing and reinforcing infrastructure, RosendaleCement.com says natural cement made a comeback: “Natural cement was reintroduced into the North American marketplace in 2004 for the purpose of enabling repair/ rebuilding in-kind to be performed on the tens of thousands of existing natural cement building and structures.”

Courtesy L.A. & Charles Berry

Natural Cement

Citing the website document, Why Use Authentic Rosendale Natural Cement, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City chose natural cement repointing mortar to replicate its original 1892 material to consciously embrace authenticity while preserving the building’s historic integrity.

“Natural cement was the predominant hydraulic binder used in the United States and Canada during the 19th century, and most of the buildings and structures built with this material remain in service today,” the document continues. “As some become due for maintenance for the first time, and others face secondary repair cycles following interventions with substitute materials, debate has renewed over best practices for the ongoing preservation of these structures.

“Historic buildings are diminished in authenticity and historic integrity when substitute materials are used without good cause,” it argues. “While it may seem intuitively obvious that replication of original materials is the simplest way to assure compatibility, this case is even more compelling for structures built with natural cement. In particular, natural cement is known to maintain low modulus of elasticity (flexibility) and high moisture vapor permeability over the long term.”

Courtesy L.A. & Charles Berry

Widow Jane Today

Since the Widow Jane Mine’s closure in 1970, Rosendale quarries have been repurposed to farm trout, store corn, and even raise mushrooms for Campbell’s Soup. But none mined one of its most melodious natural assets: acoustics.

The Widow Jane’s 19th-century natural cement mine has become a 500-seat performance space and one of the most unique 21st-century venues in New York’s mid-Hudson Valley. The 1997 album, From the Caves of the Iron Mountain, by King Crimson bassist Tony Levin, Woodstock drummer Jerry Marotta, and bamboo flutist Steve Gorn, was recorded at the Widow Jane Mine and incorporates its natural cave sounds.

Not This JaneSpeaking of… Widow Jane Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey is not made with water from the Widow Jane Mine but is from water, supplied by Turco Brothers, from a Rosendale mine on the same geologic shelf. But the legend promulgated by the bourbon may be – more sober historians like Lowengard observe – watered down: “In 1979, the last Rosendale limestone mine closed. Owner A.J. Snyder was as tough as the material he quarried and was known as a cruel boss and even crueler husband. On the other hand, his wife, Jane, was a beacon in the Rosendale community and beloved by all for her kindness and pure spirit. Hence when Snyder passed, the Rosendale Limestone Mine became known as the Widow Jane Mine.” Except that no A.J. Snyder connected to the mine ever married a woman named Jane. Next round, Mr. Lowengard, is on us. |

A Natural Amphitheater

“We are cementing history and the arts,” says the nonprofit CHHS. The cavernous room-and-pillar construction of the Widow Jane Mine serves as a natural amphitheater with an earthy resonance. The original sloped floors afford unobstructed views of a stage while the mine’s underground pool serves as a reflective backdrop for the natural light that filters in through separate openings to the outside.

“Experiencing a performance there is unparalleled,” says Eve Minson, of Hurleyville an hour southwest of the mine.

“We enjoyed attending drumming concerts in the Widow Jane Mine. The acoustics were fantastic,” remembers Diane Morrison, a former elementary teacher in Kingston City Schools.

Patricia Johnson Frankfort, who studied Fine Arts at SUNY-New Paltz, recalls a memorable Taiko Masala Troupe performance inside the Widow Jane Mine three years ago to benefit the Century House.

Geology Day at the Widow Jane Mine

And, if last year is any indication, before the mine rocks with music in 2025, rock hunters should be able to look forward to an Opening Day History and Geology Walk cosponsored by local organizations like the Wallkill Valley Land Trust.

Donald M. Arrant, Jr., of Beacon, proposed to the woman who became his wife at the Widow Jane Mine. He was working at the time as a livestock manager at a farm outside of nearby Cold Spring and knew of the mine’s history.

“It was on a whim. I thought it a good spot to propose,” he said. “There was some loose symbolism I was reaching for.” Whether that was ‘until death do us part,’ or ‘solid as a rock,’ the two will celebrate 11 years together in May.

Somewhere that old newlywed Jacob Louw Snyder is smiling.

This story about the Widow Jane Mine & Snyder Estate previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe! Story and photos by L.A Berry.