Meet willemite (Zn 2SiO 4), a zinc silicate mineral that responds to ultraviolet excitation so well that it will sometimes glow for over a dozen hours. Another odd property of willemite is visible when you strike a massive chunk with a hammer. It will briefly phosphoresce.

Willemite and Franklin-Sterling Hill Connection

Mention willemite to any collector, and, likely, they’ll instantly think of Franklin-Sterling Hill, New Jersey. That’s because these are the only deposits where it is the primary zinc ore.

It is no accident that Franklin, New Jersey, is the “Fluorescent Mineral Capital of the World.” After all, the twin complex zinc-iron deposits of Franklin-Sterling Hill have managed to produce something over 70 minerals that respond to some form of ultraviolet excitation. But you have to wonder if Franklin would be so honored to be this specific capital if willemite did not respond to ultraviolet excitation.

The fluorescence of this zinc silicate is so dependable at Franklin that ultraviolet light is present on the picking table to beneficiate the ore as it comes to grass. Willemite’s importance in New Jersey is its zinc content. The two New Jersey deposits of Franklin-Sterling Hill were the only major producers of that useful metal.

Finding Willemite

The discovery of willemite took place in a small locality near Altenberg, Belgium. When found, it was described as a siliceous silicate of zinc and later named for Belgium’s King William I.

DR. ROBERT M. LAVINSKY, ARKENSTONE GALLERY OF FINE MINERALS, WWW.IROCKS.COM

The New Jersey deposits were known to the indigenous peoples before Europeans arrived. When Europeans came to the region in the 1600s, the Dutch were said to be in control, but evidence of their mining activity is sketchy at best. During the 1700s, serious mining started but not for zinc, as open-pit methods were used to mine small deposits of magnetite. The iron ore was smelted in small furnaces that gave rise to the original unofficial name, Franklin Furnace.

The men who served as the first smelters made attempts to include the abundant complex ore franklinite, but the zinc content gave the men fits, as it formed completely useless slag-like remains. It wasn’t until the mid-1800s that studies of franklinite ore resolved the smelting problems, and zinc mining could commence in earnest.

Willemite’s Fluorescent Properties

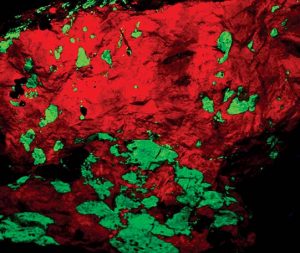

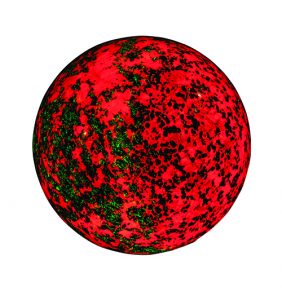

Willemite can be a significant fluorescent mineral. Under short wave ultraviolet light, it often appears as a brilliant green. The response only diminishes when there are differences in the impurities in the zinc silicate structure. The chromophore manganese causes a fluorescent reaction.

Willemite’s almost constant companion in the New Jersey region, calcite, responds to the chromophore presenting as bright red. The percentage of manganese impurity in these fluorescent minerals determines the strength of the response. About three percent of manganese in the structure gives the ideal result. Iron has the opposite effect, diminishing the fluorescent response.

Willemite Shapes

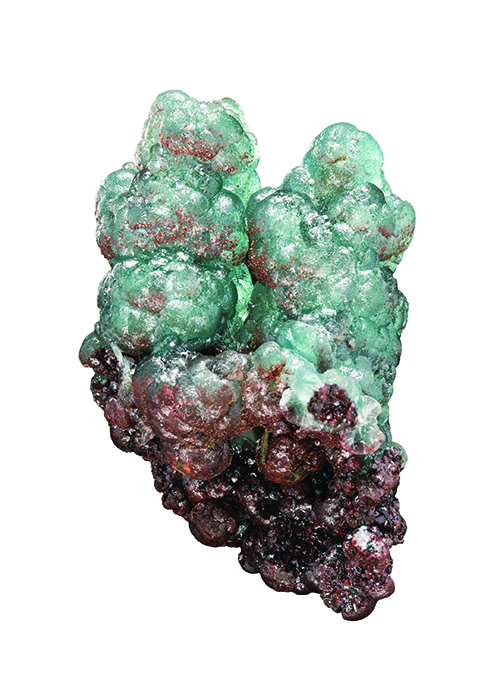

Usually, while showing rhombohedral terminations, willemite crystals form in a hexagonal shape. Small gemmy crystals are also found in a few localities, like Franklin and the original European source, and they are often colorless and usually prismatic. However, such crystals are uncommon at Franklin-Sterling Hill, as the New Jersey crystals are often crude and opaque. In this region, most willemite has formed in Franklin limestone and marble, and have been etched out or chipped to expose their complete form.

Willemite is found abundantly in this locale in a dozen different forms, ranging from small and gemmy as uncommon textbook crystals in narrow seams to big ugly rounded crystals embedded in calcium carbonate. This mineral is also prolific in solid veins, chunks, masses, and even small isolated spots in the ore. Because of its response to ultraviolet, it is easy to spot.

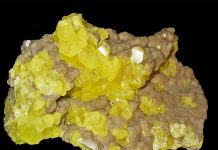

Willemite Colors

In terms of color, willemite exhibits a range from colorless, pale green, and yellowish in nearly perfect small crystals to pale green, green, dark green, red-brown, even black in the large crystals and masses. Yet, when one thinks of willemite crystals, what comes to mind immediately are big, slightly rounded blunt hexagonal crystals with rough prism rhombohedral faces that are some shade of red or reddish-brown, due to iron in the structure.

Willemite or Troostite?

For decades the red-brown willemite crystals from the New Jersey deposit have been referred to as troostite. While troostite is now a discredited mineral name, it does have a historical connection to identifying additional minerals in Franklin. G. Troost, a researcher who studied Franklin minerals and published several articles on the topic, concluded that all of the large-sized red minerals from Franklin were a specific mineral.

Eventually, they became known as troostite. The name stuck even after scientists sorted things out and showed the red crystals were willemite.

Exploring Sterling Hill – A Personal Story

After the mines in this history-making area closed, this writer was privileged to travel deep underground at Sterling Hill for a collecting excursion, before the groundwater rose and nearly filled the mine. Shutting off the pumps allowed groundwater to rise, slowly sealing the lower workings forever. During my visit in 1987, one of the owners, Dick Hauck, escorted me underground to collect, which included descending to the 1,800-foot level. We had to use ladders to descend into the mine since the incline haulage equipment was not available. Dick and his brother, Bob, purchased Sterling Hill mine at auction and turned it into a fascinating museum.

At the 1800-foot level, we were able to see the water level in the next level down, but we had plenty of time to explore and collect. With only a hammer, chisel, and ultraviolet light, I was able to locate a nice small vein of calcite-willemite and chop out a few pieces of ore, remembering I had a 1,800-foot vertical climb to make to reach daylight. That was quite a fun trip!

Finding Willemite Specimens

A fascinating feature about Sterling Hill is the exposed wall of the surface property. These deposits were well known because of the indigenous peoples and later arriving Europeans who were exposed to the ore veins. Lighting one outside wall with ultraviolet shows a marvelous streak of fluorescent minerals.

Though both mines are long since closed, collectors still find success in locating good specimens by working the remaining dumps in the mining area. A small digging fee is required, but the dumps are still fruitful from decades of active mining.

While there’s no question willemite is a popular and prolific mineral in the Franklin-Sterling Hill deposit; it’s also present in many mining localities. Although any deposit rich in zinc might produce willemite, it is just a minor product of weathering. Using shortwave portable ultraviolet lights while checking several well-documented silver mines in Arizona, willemite often shows up intimately associated with other minerals, like red fluorescing calcite, blue fluorescing fluorite and even some types of clay.

Willemite Mined In Tsumeb

Another major source of willemite was Tsumeb, Namibia. Tsumeb willemite differs markedly from that of the New Jersey species. Tsumeb willemite does not fluoresce. There are also no records of large crystals, and many assume the willemite in this locale is all secondary, unlike New Jersey, where much of the zinc silicate is considered primary.

Tsumeb is unique because the deposit has three separate oxide zones because of North Break Fracture. This huge fault brought atmospheric oxygen and surface moisture deep underground, resulting in an attack of the primary sulfides. Also taking place at this time was weathering of the ores, which created a wonderful array of superb secondary species, including willemite, and even more importantly, smithsonite. Germany took over operations of the mine in the early 1900s, only to lose it after World War I.

When Tsumeb crystals were found, they were seldom as much as a centimeter long, and their color ranged from white to yellow. Generally, the willemite found in Tsumeb is white in small needle sprays within tufts on a matrix. Occasionally the needles reach a centimeter but are usually smaller. Another form of willemite appears in rounded or curved surfaces, and sometimes as complete balls. These can be of different colors from green to bluish.

Standing out from the Crowd

Without the specimens from Franklin-Sterling Hill, willemite would only be another unusual species and not the major collector species we enjoy. Only from New Jersey does it cause great interest, curiosity, and even excitement among collectors because of its colossal crystal size and brilliant red and green fluorescent crystalline masses of calcite and willemite.

While the Franklin, Sterling Hill deposits are the subject of several studies, admittedly, the most accurate and complete research of the deposits was done by Dr. Peter Dunn, noted researcher based at the Smithsonian Institution. Frequent interviews and discussions with locals, miners, and collectors, helped Dr. Dunn assemble an exceptionally comprehensive group of texts on these complex and historically essential deposits. For students of fluorescent willemite and the Franklin-Sterling Hill zinc deposits, Dr. Dunn’s work is the most comprehensive research work available.

This story about willemite previously appeared in Rock & Gem magazine. Click here to subscribe. Story by Bob Jones.